How to survive as an indie developer for 20 years

"Size Five has always just plodded along without a colossal success, which is fine by me. I'm still here."

Dan Marshall was 24 when he picked up C++ for Dummies. "I've left this too late," he thought. "I'm too past-it to be learning a new skill like programming. Damn it, why didn't I learn this in school?"

Two decades on, Marshall has led the development of no fewer than three games with 80+% review scores in PC Gamer's pages. It's a rare distinction—as is the 26% he was awarded for Behold the Kickmen ("A misguided attempt at parody, underpinned by a poor sports game by anyone's standards," tutted our reviewer). With the help of a small gaggle of collaborators, Marshall has weathered 20 years in the hairiest, most volatile entertainment industry imaginable. Despite the countless office chairs sitting empty in the premises of once-promising studios, Marshall is still here.

Size Five Games began as a hobby. "It never even crossed my mind to talk to publishers in those days, if I'm honest," Marshall says. "It was all still doable in my pants in my spare room, at the time we did Ben There, Dan That! and Time Gentlemen, Please!. Those games didn't cost me anything."

In his evenings and weekends, Marshall was working to revive a LucasArts-style adventure genre that, before the days of Kickstarter, had been abandoned. "Point-and-clicks are weird, in that they died between the years of about 1995 and 2002, so not very long," he says. "But it felt like this gulf of time since anyone had made a proper 2D one."

Ben There, Dan That! and Time Gentlemen, Please! established Marshall's comic voice—the breezy, flippant dialogue which has been the glue across a range of projects in dramatically varied genres. The two games also set the financial foundation that Size Five has been building on ever since. There was a time when, if you filtered Steam games by Metascore over 80% and price under $5, Time Gentlemen, Please! rose to the top of the catalogue. "It hit a sweet spot," Marshall says. "Which in terms of getting bums on seats was like gold dust for me."

However, it wouldn't be true to say that Dan and Ben, the comedic counterparts of Marshall and fellow writer-designer Ben Ward, have become household names. "It's really frustrating, but no one remembers in a lot of ways," Marshall says. "You see people doing paintings online, like, 'I painted every indie game character in the world'. And Ben and Dan are never in it. No-one does fan art or anything. But they're quite well regarded among people who've played them."

No-one does fan art or anything. But they're quite well regarded among people who've played them.

Dan Marshall, Size Five Games

The professionalisation of Size Five Games—still known as Zombie Cow in the late noughties—came with a diversion into edutainment.

"[UK broadcaster] Channel 4 was putting out all this educational content at like 10:30 am on a weekday," Marshall says. "So no one's watching it, right? How do you engage with kids of a certain age, with your public broadcaster remit?" One proposed answer was Privates, a free twin-stick shooter in which you control a squad of tiny Marines wearing condom hats. Your soldiers storm into vaginas and rectums to kill sexually-transmitted infections. "To a certain degree, it worked," Marshall says. "Privates had quite a big reach, comparatively."

Marshall's comedic immaturity made him the perfect person to communicate important information to teens. But it also left him ill-equipped to handle accountants and lawyers and "meetings with Channel 4 about what happens if the Daily Mail finds out". He was suddenly pulled into a much more grown-up world than the one he had known as a point-and-click hobbyist.

"You're explaining jokes, and you're suddenly painfully aware that, no matter how funny the script is when you play it in the game, it's not when you're sitting in front of someone in a suit," Marshall says. "They just have this look on their face of, 'You silly little boy. I'm a real grown-up with a real job, and sorry, you want to give them little condom hats?'"

But the lessons of that period were extremely valuable and helped ensure Size Five's longevity. "If you're making stuff, no matter how much you're doing it in isolation, there's this wider world," Marshall says. "If you're dealing with Steam, you've got to sort out your American tax affairs. It's boring, but they've got to know what you're doing.

"I deal with people today who are just making basic mistakes, in terms of, are you legally covered for stuff? Which is a constant thing you've got to be aware of when you're making videogames. Have you got the forms signed for this voice actor? Have you got the rights to use that footage in your trailer? And you see people who are just winging it."

Other hard lessons followed Privates—as with the side-scrolling multiplayer shooter Gun Monkeys. Designed for two players, Marshall intended it to be an explosive meeting place for pre-arranged sessions between friends. "But then you suddenly have a load of people with the game, and that's not what they want to do," he says. "All their friends are busy, they bought this game and they want to go play it. They log into the server and there's no one else there, because it's three o'clock in the morning in Germany."

It's the sorry experience that many indies have had with multiplayer projects. Unable to pull in the player numbers required to guarantee busy servers at all hours, they watch their audience dwindle away into nothing.

"It was constantly extremely frustrating for me," Marshall says. "I wouldn't touch multiplayer with a barge pole ever again. It's not in Size Five's budget, basically. Even with the tools you can get today, it's not a viable path, I would suggest, for the sweeping majority of indie developers. It's hard to make, it's hard to market, and it dies. There are multiplayer games I know of that came out when I was making Time Gentleman, Please! that died a decade ago and have not made any money for 10 years."

I wouldn't touch multiplayer with a barge pole ever again.

Dan Marshall, Size Five Games

Marshall acknowledges that, with Gun Monkeys, he bit off more than he could chew. "But if there's one thing I'm really proud of about Size Five, it's that there's no guessing what's coming next," he says. "It irritates the shit out of people, but as someone who loves videogames, I don't want to play the same fucking thing over and over with a different skin on it. So I've always tried to do something a little bit stupid or a little bit different. Even if it fails, it's still a success in my eyes, because it's not the same thing that someone else has done before."

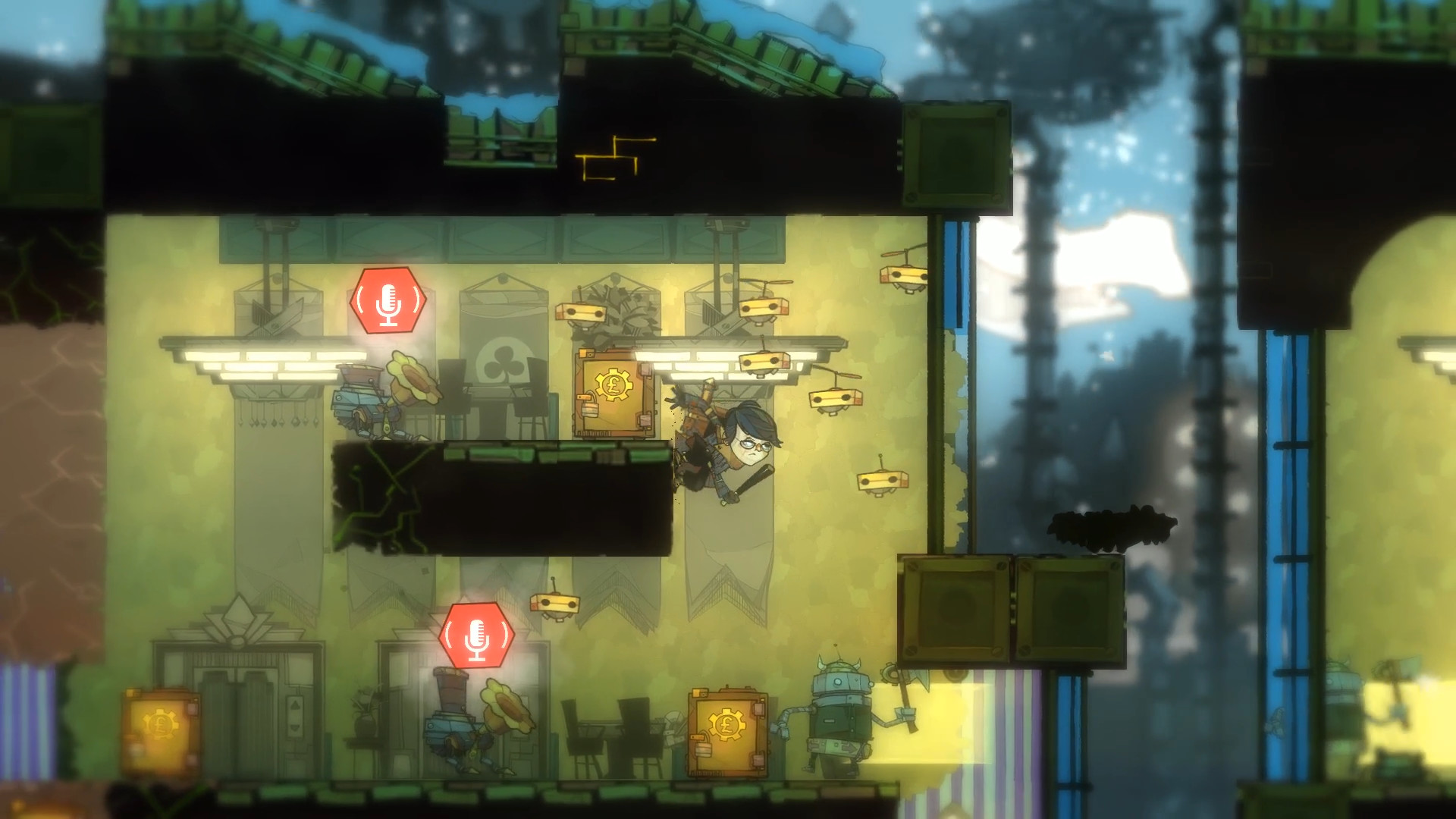

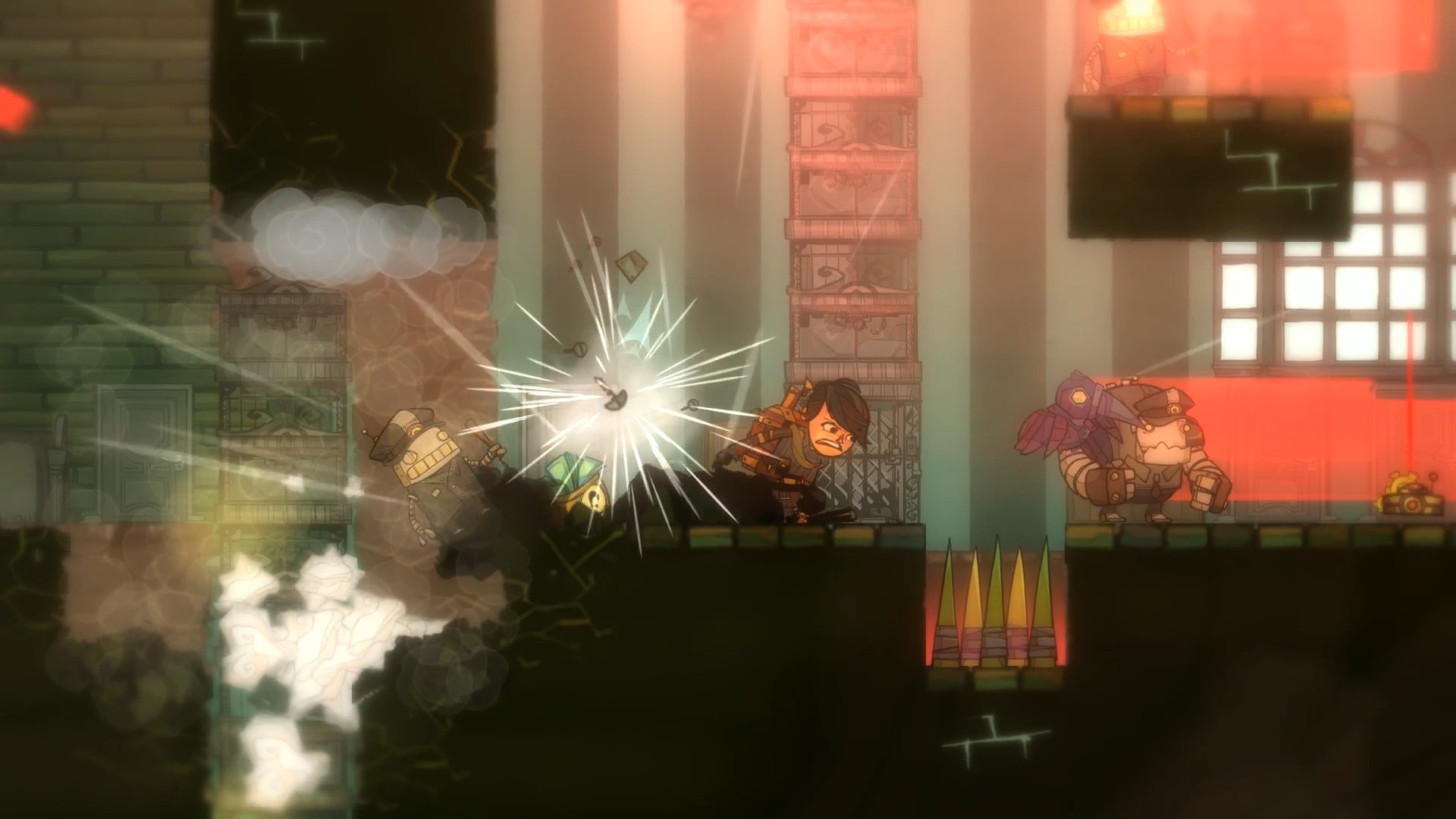

The Swindle, a Spelunky-esque platformer with a stealth twist, is a perfect example of Marshall's commitment to that bit. It asked players to thwart the development of an anti-thievery AI at a steampunk Scotland Yard, and gave them a hard limit of 100 tries in which to do it.

"People fucking hated that," Marshall says. "The mistake I made was locking the good controls behind upgrades. You're this bumbling idiot at the start, and then you get good through upgrades, which is daft. Because people see that they haven't done very well yet and go 'I've only got 79 days left!' And it's this weird psychological thing where they think they need to be 90% of the way through the game after 20 days have gone. But you know, I hadn't played anything that did that."

The response among critics and players was polarised, yet The Swindle was Size Five's greatest financial success. "The people who love it fucking love it," Marshall says. "There are people who have played more hours of that than I can understand. And that's the game that did get fan art. So The Swindle certainly propped the company up quite a lot."

In less successful moments, Size Five has been sustained by a certain thriftiness—hiring in outside help with music, art or code only in short bursts. "Until very recently when I took on employees, it's always been just me sitting here typing, and that's why my overheads are so low," Marshall says. "And I think that's probably the key."

"You see so many indie developers who rent out an office, down by the river in London. And they go and take their game to PAX, spending thousands on airfare and hotels, let alone the cost of the conference, and printing the big fucking banner out, and having someone standing there in front of their build for three days. These things are just astonishingly high cost. If I wanted 10,000 people to play my next game, the worst way to do it would be to fly to Boston and stand next to it."

Marshall wonders whether Size Five's endurance can be credited to those meetings with men in suits about condom hats. "And working out very quickly that how to run a business is not spunking money," he says. "You've got to be very careful where every quid goes."

The studio's breakthrough smash hit has never quite arrived. This despite Marshall and Ward making their masterpiece a few years ago in Lair of the Clockwork God, an exquisitely smart and funny adventure that blends point-and-click mechanics with platforming. "Critically, it did really well," Marshall says. "It's probably the game I'm most proud of. I would say it didn't sell as well as the reviews would imply it should have done. And that's frustrating, because what's that barrier that stopped people taking a plunge on it?"

If he had his time again, the one thing Marshall would alter about Lair of the Clockwork God would be its protagonists. "It was only after launch that I realised that, if I'd just changed it to two other guys—it wouldn't have taken that long, it could be Bill and Frank, quite happily—it would have possibly done better financially. It did fine, it didn't die on its arse and didn't make me rich, it's somewhere in between. But that's the one thing I think, going back, I would change. Because no matter how hard we tried to say, 'This isn't the sequel to these two games,' people who hadn't played the first two steered clear of it."

One of my biggest worries in life is all this comes crashing down, and I've got to get a real job where I'm not the boss.

Dan Marshall, Size Five Games

A constant of Marshall's career has been the nights when he lies awake, sweating, wondering whether the next game is going to sell any copies. "One of my biggest worries in life is all this comes crashing down, and I've got to get a real job where I'm not the boss," he says. "And I don't necessarily work from home, in my nice little house in the middle of the countryside. I might have to commute for an hour and a half every day, to go into the office. I don't want that."

But when he follows the thought all the way to the end, it doesn't sound so much like an ending after all. "Even if the worst thing happened and I didn't have any money, I would be coming home and making games in the evening and over the weekends," he says. "I would make something small and stupid and fun and put it live, and Size Five would carry on."

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.