Exclusive: New god game Demiurgos puts you in control of a famous deity trying to outplay other gods on a cosmic tabletop version of earth

It's a promising new blend of strategy and simulation from a god's-eye view.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

The god game is a strange, beloved, and deeply PC niche. It's torn between the tensions of being a strategy game and a world simulator. Demiurgos, the next game from the developers of Martian terraforming sim Per Aspera, is revisiting playing god with a mix of old and new ideas that—after a few hours with an exclusive early build—I think will appeal to a lot of players.

As you go forward your worship spreads, but the world also grows completely independent of you

"We have always loved god games, but there have not been many god games lately," Tlön Industries designer Javier Otaegui told me early on in our conversation.

The Per Aspera dev has gotten bigger since its debut and is now developing multiple games, but it's clear that the same studio that once made a game with an accurate topographical map of Mars hasn't narrowed its ambitions. Because, obviously, the step up from simulating one barren world is simulating the deities playing around with new ones. Which is, given the nature of polytheistic gods, a competition.

"The gods are playing a tabletop game," said Otaegui. "I wanted to make a kind of a game based on the Bronze Age. So we started thinking about different ideas, and we found yeah, a mythological deity game set in a simulated Bronze Age, using Bronze Age aesthetics for the humans. And we thought it would be funny to move from a realistic 3D spherical planet, to a like, kind of flat earth."

At the start of a game of Demiurgos you pick out a god from a selection of historical pantheons, each with their own set of unique modifiers and powers. Poseidon, for example, can more readily cast his powers near oceans, while Anubis can more readily stockpile and make use of mortal souls as a currency.

The world is then spread before you: An array of islands populated by little Bronze Age tribes in their tiny settlements—just a dozen people or so, in the early game. Your god reveals themself in one, creating their first priest, who starts converting locals to your worship, and then you're off to the races. Literally—Demiurgos is a real time game, so the simulation layer starts ticking right off.

Mold the world, change the people

You use basic powers at first, like blessing people to keep them healthy, giving them a motivational shock, or—for particularly chaotic gods—simply hurling fistfuls of resources from nearby deposits. Nothing says "worship and fear me" like the mayor declaring you need to build a new hunting cabin shortly before a rain of logs lands on the construction site.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Later you pick up greater powers. Civilization-focused things like commanding people change their jobs, founding new cities, forcing armies into berserker rages, or making a specific human immortal. There are also the requisite natural wonders—tornados, earthquakes, meteors, blessed harvests, spirits of luck, and rampaging monsters.

As you take actions the world responds, with more people coming to believe in you. At the same time your god develops their karma—chaos and order, good and evil—with bonuses and penalties for using powers that are in or out of character for them. Babylonian civilization god Marduk, for example, only cares about order—good and evil are irrelevant to him—while jolly Poseidon is a deity of good, but also chaos.

"We kind of used the classical alignment system so people could also find something easy to relate to," said Otaegui.

In the process of finding the fun we leaned to where we are now, which is like a long match would be six hours, eight hours tops

Javier Otaegui

As you go forward your worship spreads, but the world also grows completely independent of you. The people have their own lives: they choose to migrate between settlements, get jobs like forager or warrior or farmer, and have children. In a way, the little citizens are playing Civilization while you're watching—they gather food to expand population and build buildings that give their city bonuses in wars or in economic production.

Their little early settlements even go to war with each other, conquering other cities to form larger kingdoms ruled from a single city. That might have a lot to do with you if you're playing as, say, god of war Mars, but who the temporal authority is might have very little to do with the goals you've set for gathering worshippers and declaring victory.

Because that's the name of the game. You win by accruing divine titles—Primordial Evil, God of Scriptures, Divine Teacher, and the like—which are all linked to reaching milestones or taking specific acts before any other god.

To do those you need your primary resources, all of which come from mortals that believe in you: a Worship currency to gain mana that casts miracles, offerings to train new priests and build temples or as sacrifice for powerful spells, influence in cities to affect their domestic choices, and precious mortal souls accrued every time a worshipper of yours dies.

That said, while it was strategic, the build of Demiurgos I played wasn't frantically competitive. It runs in real time, but I wasn't counting my actions per minute like it was Starcraft.

"I think that god games have a quality, and actually this may be in general for life simulations, which is that there should be a contemplation value to it. I mean if you just want to contemplate and see what your ants are doing," said Otaegui.

"It was really hard to find [that pacing balance]. I mean because there is this big tension between god game and strategy which is kind of represented in the simulation versus the high, abstract strategy. So yeah, finding the right place was what we have been doing for the last couple of years."

I found the balance really interesting and quite compelling. I was able to speed up to execute larger plans, then slow the simulation down, even pause it, to get an idea of what was happening around the little flat world and watch the fallout of my actions.

What happens if I make a mountain pass between two kingdoms that can't reach each other, then send my priests over? What happens if I lay down a magical totem to turn that lush grassland on my enemy's capital into a harsh desert?

A lot of Demiurgos focuses on where you have worshippers, as the greater a concentration of them exists the wider your circle of influence spreads, and you can only cast miracles inside that circle. Closer to your worshippers, the cheaper miracles are—only a handful of your powers, those generated passively over a fixed time, can be used anywhere in the world. Otherwise you need believers present to work your wonders, incentivizing you to grow your faith far and wide while stacking worshippers in crucial cities to ensure that your powers are as cheap as possible there… or not, depending on how you've built your god's powers from the skill tree.

Playing as Marduk, for example, my powers had most effect when I could use them in large cities. It didn't really matter who was worshipped in the countryside if the king and his immediate subjects were taking orders from me. As Poseidon, though, the ocean always counted as a place of strong worshippers for me: So worshippers spread around thinly at every coastal city in the world let me use powers all over the place for cheap.

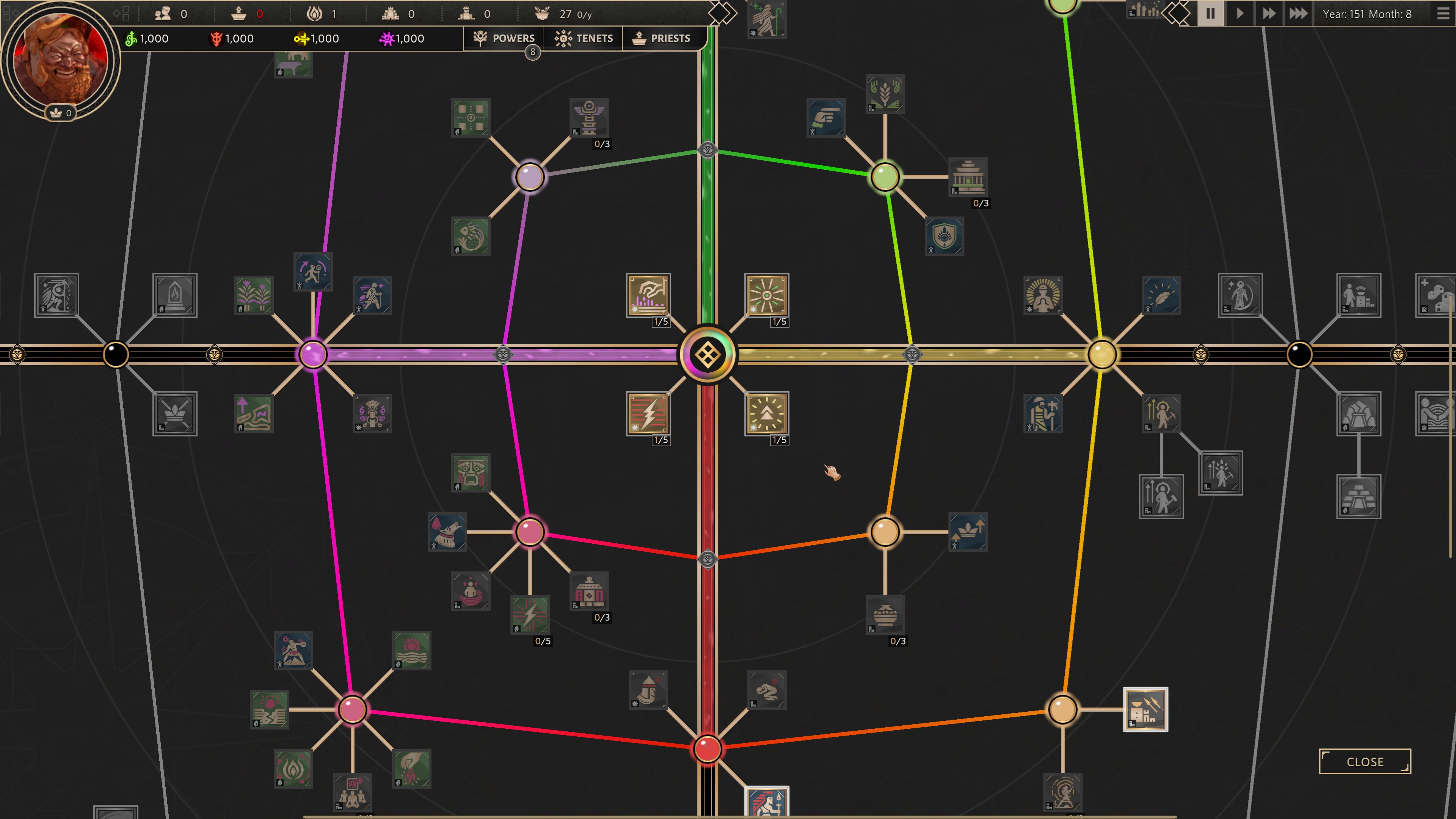

It comes back around to that karma system. Your actions accrue karmic points and unlock new branches of a big, four-quadrant skill tree along the good, evil, chaos, and order axes. Nature-focused powers lean toward chaos and civilization-shaping powers lean toward order. Calling down a meteor is firmly in the evil chaos quadrant, while multiplying a city's bread stores falls in good and order.

I particularly loved one part of the game: Priests. The little people who inhabit the world have a bar for their beliefs, and once it's over 50% you get that little person's worship. Your priests convert people over time, a steady uptick in belief, while miracles tend to hit them with big, one-time chunks of faith.

"That's how you spread your word, your religion. The most effective way," said Otaegui.

Priests are the only people in the game you can really directly control, sending them between cities and upgrading them to advanced forms like fast-converting Missionaries, karma-balancing Shamans, prayerful Monks, and enemy-seeking Holy Warriors. Backing up your priests by having cities build temples, shrines, totems, altars, and reliquaries dedicated to you lets your faith anchor itself in the world.

Meanwhile, the other gods are sending their priests around to do the same, and compete for the same people and builders. There are even pesky philosophers who'll return people to an atheist, godless state!

It's important because to survive your god has to set up a passive source of new worshippers—and that's what priests are. While early on you can keep easy track of worshippers, those tribes of a dozen will explode, as a Bronze Age civilization does, to cities with hundreds or even a thousand little inhabitants that rise or fall as they trade hands between kingdoms. Your god becomes more powerful over time, but by the late-game mankind is a vast swarm with its own goals and ambitions where only the most powerful miracles can nudge the faith meter of a whole city's population at once.

A world in a capsule

Growing a flock of priests and scaling my miracles alongside the exploding population was compelling stuff, and it didn't overstay its welcome either. By the time your world's little map becomes that complicated and busy it's almost certain that one of the gods is close to winning the match. I asked why, though, Demiurgos cuts out when it gets to its most complex—many strategy players love a game that's 20 or more hours long per campaign.

"In the process of finding the fun we leaned to where we are now, which is like a long match would be six hours, eight hours tops. When we finish the game, we'll know exactly how [long]," he said.

It could have been a much longer game, said Otaegui, but rather than padding out the playtime with busywork Tlön focused on making a game where you can play many matches as different gods with different playstyles, and even play the same god in several different ways.

"We decided to listen to the game and make every minute that you're playing be fun."

We try to be as broad as possible with the idea that every single god would bring their own personality, their own play style

Javier Otaegui

For now, they've announced five gods—Marduk, Poseidon, Anubis, Loki, and Mars—but a peek behind the scenes at unfinished deities showed me they're certainly aiming for quite a few more, including some truly choice selections from across global myth. Their goal with the playable gods seems to be good variety, yes, but also player expression.

"We try to be as broad as possible with the idea that every single god would bring their own personality, their own play style, and maybe even discovering new play styles for different kinds of gods," said Otaegui, "We also did not want to make them very strict in in how they need to play."

An unfinished taste was all I needed to know that I'm destined/doomed to spend a few hundred hours with whatever Tlön Industries releases as Demiurgos's final form. The team is currently working on a demo for Demiurgos to release sooner rather than later, and have just released its first proper trailer. Tlön is hoping the finished game will be in your hands next year.

Jon Bolding is a games writer and critic with an extensive background in strategy games. When he's not on his PC, he can be found playing every tabletop game under the sun.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.