D&D is quintessentially American and Warhammer is quintessentially British

D&D is Vincent Price in The Raven, Warhammer is Vincent Price in Witchfinder General.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Every now and then one of my American friends will admit to me, with a slight sheepishness, that they don't really get Warhammer. They didn't grow up with it and now there's so much of it—a far-future science-fantasy setting, two fantasy settings (one of which has been re-released as a prequel to itself), and a football-themed parody of one of those fantasy settings—and they don't really understand its whole deal.

The older generation of my British friends, the ones who grew up before Dungeons & Dragons became mainstream with its fifth edition in the 2010s, find D&D equally bewildering. Most have belatedly tried it out, but there's a barrier there. They got into tabletop gaming via Warhammer and Call of Cthulhu and Vampire: The Masquerade and etcetera, and D&D has a flavor that's different enough to be off-putting. While obviously Warhammer's roots are British and D&D's are American, the degree to which that defines them is maybe not apparent to everyone.

For instance: American game developer Zach Barth, of videogame studios Zachtronics and Coincidence, once outlined a pitch for a Warhammer 40,000 game to Games Workshop. The creator of automation puzzle games like SpaceChem, Infinifactory, and Opus Magnum thought it might be fun to make a game about playing a junior tech-priest in the 41st millennium, but wanted it to be a "workplace comedy, except that it's set in a Warhammer 40K factory, where you're pumping out power armour and stuff."

Barth had concerns about how this would be received. He asked a Games Workshop representative how the company would react to a pitch for a "funny" Warhammer 40,000 game. The response he got back was, "They're all funny, it's a funny setting."

Barth was shocked by this. "I'm just like, I don't know if Americans see it that way!" he said.

To understand why that sense of humor doesn't always translate, first we need to look at an example of just how American the assumptions behind D&D can be.

You all met at an inn

A lot of Dungeons & Dragons games start in an inn. Even the ones that don't soon arrive at one. It makes sense: one of the first things the hobbits do after setting out in The Lord of the Rings is stop at the Inn of the Prancing Pony. And like the Prancing Pony, the default inn from a game of D&D comes with a hooded stranger in the corner as a standard part of the package. He's practically furniture.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

But everything else about the Prancing Pony is part of Tolkien's idyllic imagining of rural England threatened by oncoming darkness. Bree and the Shire are the land of Tolkien's youth, of village pubs and greens being put at risk by dark modernity and industrialization. This is where Dungeons & Dragons diverges: the average D&D tavern is a place where you open the door and everyone stares at you and the piano player stops mid-tune. There will be a brawl, probably within minutes.

It's not the Prancing Pony. It's a saloon from an American western transplanted into a different genre, like the cantina from Star Wars.

In 1987, White Dwarf magazine published an adventure for Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play set entirely in a tavern. It was so popular it was reprinted several times and eventually became the basis for a whole series of adventures in the same format. Called A Rough Night at the Three Feathers, it's about multiple plots taking place in one building over the course of, as the title suggests, a single rough night. There's a scandalous affair, a dead body, mistaken identity, cheating at cards, and the whole thing's triggered by a noblewoman and her gigantic entourage being crammed in with a bunch of commoners for a night.

It's not a scene from a cowboy movie transplanted into a fantasy world, it's a hotel farce transplanted into a fantasy world—an episode of Fawlty Towers where nobody can mention the warhammer. It's a type of humor that relies on an understanding of social class deeper than being able to tell he's the Emperor because he's the only one not covered in shit, and it applies to every faction in Warhammer.

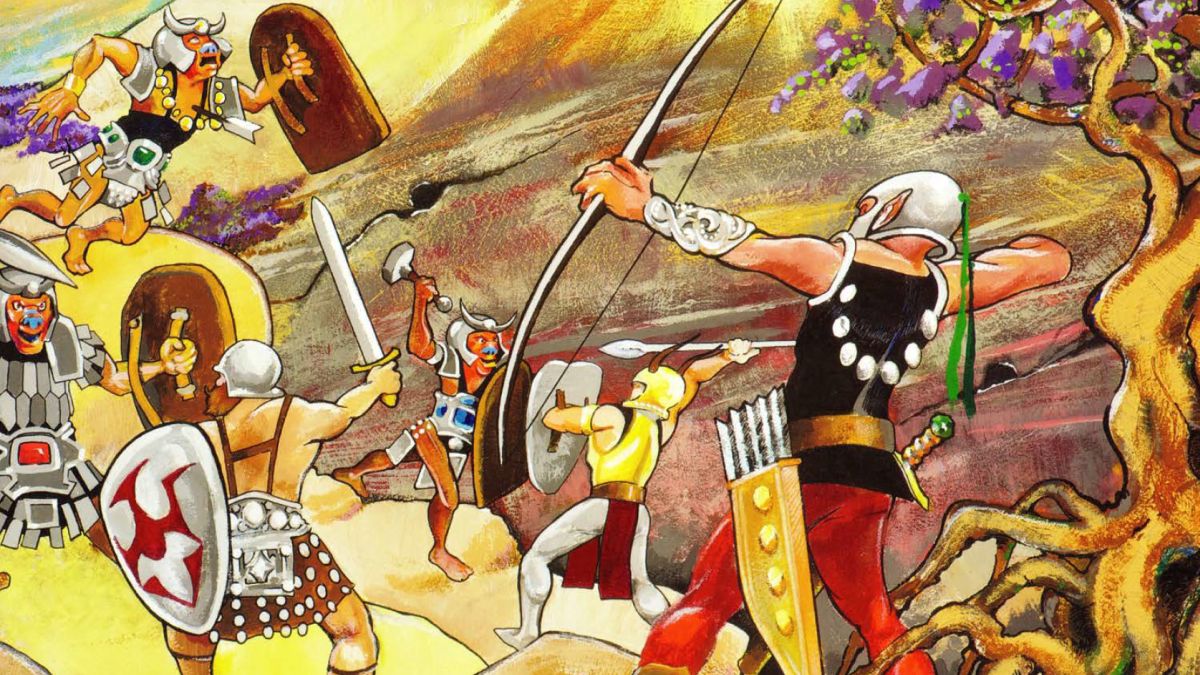

Paul Barnett, as general manager of Mythic Entertainment when it was creating Warhammer Online, had the job of explaining this to Americans at E3 in 2006, and handled it enthusiastically. Warhammer's orcs, he said, were "soccer hooligans" while its dwarfs "are like the northern working class of England," who are "very proud of their holes in the ground." Meanwhile, "The high elves are British posh people. Never done a day's work in their lives, don't understand about doing the washing."

Finally, "The dark elves are English posh people what have taken drugs."

As well as the broad class satire, there are incredibly specific digs like the villainous Een McWrecker being based on Ian McGregor, who was head of the National Coal Board during the miner's strike of 1984-85, while Empress Magritta is based on Margaret Thatcher. It's not just British, it's extremely 1980s British, with a particular visual and topical debt owed to that era's New Wave of British Heavy Metal, a debt it repaid by licensing out Warhammer art for releases by Bolt Thrower and Saxon.

With all these hyper-specific references, it's no wonder Americans don't always get Warhammer. If you're not familiar with Zulu, Bernard Cromwell's Sharpe books, and season four of BlackAdder, then the way 40K's Astra Militarum parodies military incompetence yet celebrates the ordinary man in the trenches yet laughs at their disposability—an entire wargame faction with the ethos of Jona Lewie's 1980 anti-war song Stop the Cavalry—must fly right past you. No wonder even a smart guy like Zach Barth doesn't get it.

Before Warhammer fans wear out their arms patting themselves on the back for appreciating its complexities, there's a lot more to unpack in D&D as well.

True Crit

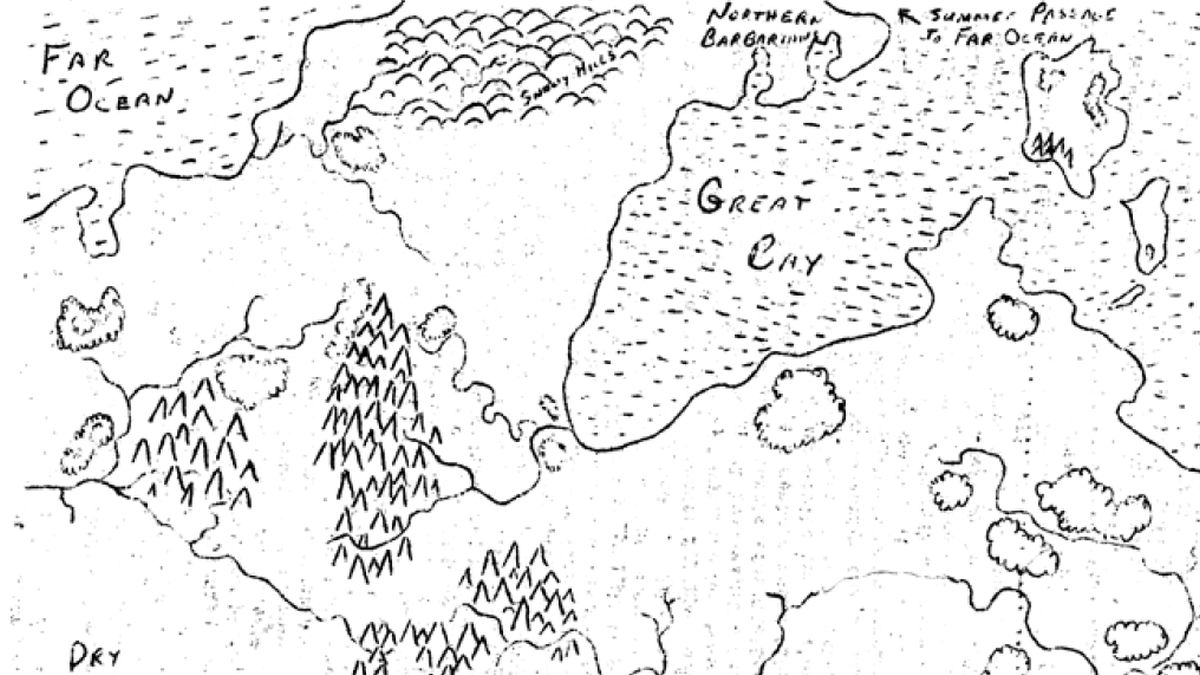

The game that would become Dungeons & Dragons was first run by Dave Arneson in the Twin Cities: Minneapolis–Saint Paul. He took it down to Lake Geneva, where Gary Gygax lived, and ran a demonstration. Arneson's game was set in and around a village called Blackmoor, and when Gygax started running his own version, he based it in and under a city called Greyhawk. The two plonked these locations down on a shared map of "the Great Kingdom" based on North America, with Blackmoor where the Twin Cities would be located, and Greyhawk positioned roughly where Lake Geneva or Gygax's home town of Chicago would be.

The bit at the top labeled NORTHERN BARBARIANS was Canada.

It's been said that Americans think 100 years is a long time while Europeans think 100 miles is a long distance. Even when they're not recycling a map of the continental United States, distance in D&D's settings is based on an American understanding of scale. Everything is a long way from everything else, and connected by wide roads. This doesn't just affect the way the maps look, but gives D&D adventures one of their foundational cliches. When adventurers aren't delving dungeons their baseline job is working as caravan guards, which can seem mundane if you don't imbue it with the romance of its inspiration: wagon-train westerns.

The tavern-as-saloon isn't the only place cowboy movies bleed over into D&D's version of fantasy. Fantasy is often about long-distance quests, and the western is another genre that treats overland travel as romantic and dangerous. Think about how many westerns involve cattle drives, stagecoach robberies, horseback posses chasing down their target, and railroads being built. When a typical D&D campaign first leaves the dungeon it becomes a wilderness adventure, and the frontier fantasy of adventures from Gygax's Keep on the Borderlands module back in 1979 to Lost Mine of Phandelver, the adventure that kicked off D&D's fifth edition, is an explicitly American one.

Look at the maps of classic D&D villages like Hommlet from The Temple of Elemental Evil. It's got four broad roads leading into it, and no ditch or wall to defend it. It doesn't look like a medieval settlement at all. It looks like Hadleyville from High Noon. It's a place ready for adventurers to ride onto its main street while the locals peer out at them from behind shuttered windows, only instead of Stetsons the riders will be wearing pointy wizard hats.

Gygax and Arneson weren't the only D&D designers whose take on fantasy comes off more American than European. The Dragonlance campaign, and the bestselling novels based on it by Tracy Hickman and Margaret Weis, co-star Riverwind and Goldmoon of the Que Shu tribe, whose culture is explicitly Native American. The setting's fire-and-brimstone take on religion, with gods who eagerly leap to Cataclysm to punish sinners, was inspired by Hickman's Mormon faith, with Dragonlance's religious texts the Disks of Mishakal an explicit reference to Mormonism's golden plates. They make for jarring blasts of USA-ness in what is otherwise a textbook Lord of the Rings knock-off.

If the British don't quite get D&D, or Americans are confused by Warhammer, it's not because they're missing something obvious. These games, despite the global reach they now enjoy, are deeply rooted in their respective national cultures. Understanding their origins, from the wide open spaces and Wild West saloons of D&D to the combination of class satire and the rainy industrial grubbiness of Thatcher's Britain underpinning Warhammer, can help bridge that cultural divide.

While D&D has broadened its scope (the cover art no longer features women who look quite so Californian), and Warhammer continues to change (the new army of Grand Cathay doesn't reference a brand of fizzy drink from Manchester) these differences remain a fascinating lens to view them through.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.