Our Verdict

This journey through a dreamscape of loss and absolution is unique, if a bit uneven at times.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A story of loss under military occupation that defies easy categorization.

Reviewed on: GTX 760, Intel i5-4440, 8GB RAM

Price: $9/£8

Developer: J. King-Spooner

Publisher: J. King-Spooner

Multiplayer: None

Link: Official site

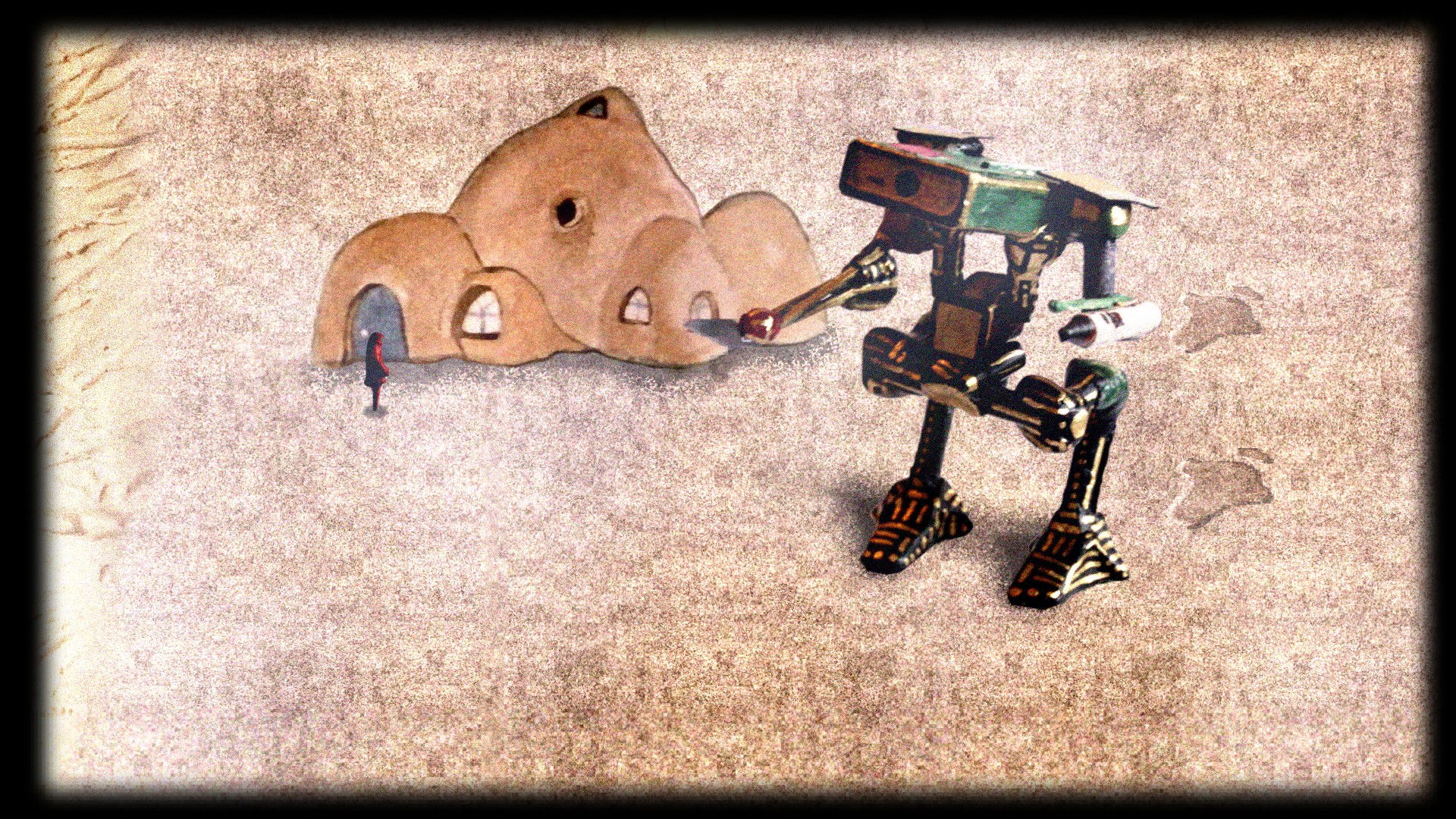

Dujanah is searching for her family through a fictional Islamic country covered in video static haze. Her husband and daughter went out a week ago to bury the family hamster, but were killed in the middle of nowhere for no reason by one of the country's occupying armies. Dressed in flowing robes and a face-covering niqab, she visits her neighbor Ted to borrow the keys to Duck, his oil-drilling robot, and pilots it out into the desert for answers.

Dujanah's search feels like a dream, a series of images linked thematically but not in any consciously sensical manner. The desert is a disorienting moire muddle. Even when riding Duck, with its whimsical biddy-biddy-bah biddy-biddy-bum walking music, it's easy to get the feeling there's nothing out there to find.

The Militarized Zone is zoomed out, making Dujanah tiny compared to the stamped-metal military buildings and tangled razorwire. The Generation Plant is a maze, populated by workers in suits with featureless yellow masks and automatons crafted from broken bits of electronic equipment. Dujanah's hometown of Touf Lajjel is relatively cheery: there's a concert—featuring random, procedurally generated music—on every city block. The girl punk scene is growing, and even the women in conservative dress are nodding along with the catchy background music. Even here, though, empty spaces contain painful memories of old arguments.

The people she meets are soft, vague clay figures. Their featureless faces seem turned inward as they muse aloud about their thoughts. The authorities who might have some insight into what's happened to her family are bizarre grotesques, made of tumorous growths or bits of broken electronic equipment. This grotesquery escalates until Dujanah meets the men in charge—the men who may be responsible for her misery. Her conservative, head-to-toe red garb contrasts with these two men, each of them a misshapen nude figure, each of them trying to drive her off as a nuisance.

What answers there are to find are in following other people's thoughts where they lead. Dujanah discovers "a version of the child expressing themself through play" and is drawn into a diorama about the nature of desire and loss. A schoolteacher muses on the difference between the love one has for a spouse and the love of a neighbor. A trio of mysterious women offer Dujanah a chance to avenge herself on those who have wronged her. Each of these conversations informs the nature of Dujanah's need to know what has happened, and to come to terms with her loss.

In so doing, the game grapples directly with itself and with being viewed. Characters muse about authenticity. A woman dreams of cracked cell phone screens. Robots contemplate their own existence, aware of the fact that they were programmed to do so. This game accepts the player's gaze and gazes back. It's occasionally distracting: for example, at one point a humanoid spider wonders aloud whether an arcade game about Muslim theology can effectively communicate its message despite being made by an outsider for a non-Muslim audience. I can appreciate Scottish creator Jack King-Spooner's perspective on my own without needing self-indulgent reminders like this.

The beating heart of Dujanah is tucked away in that arcade, in Touf Lajjel. Here, six games each offer a different perspective on her journey. A clone of Missile Command has exactly the same moral as the game it's based on. A crude joke game hides a half-remembered narrative about attempting in vain to live up to the expectations forced on you. A racing game, reminiscent of Mode 7 games on the SNES like F-Zero and Super Mario Kart, chases after something that a video game can't deliver.

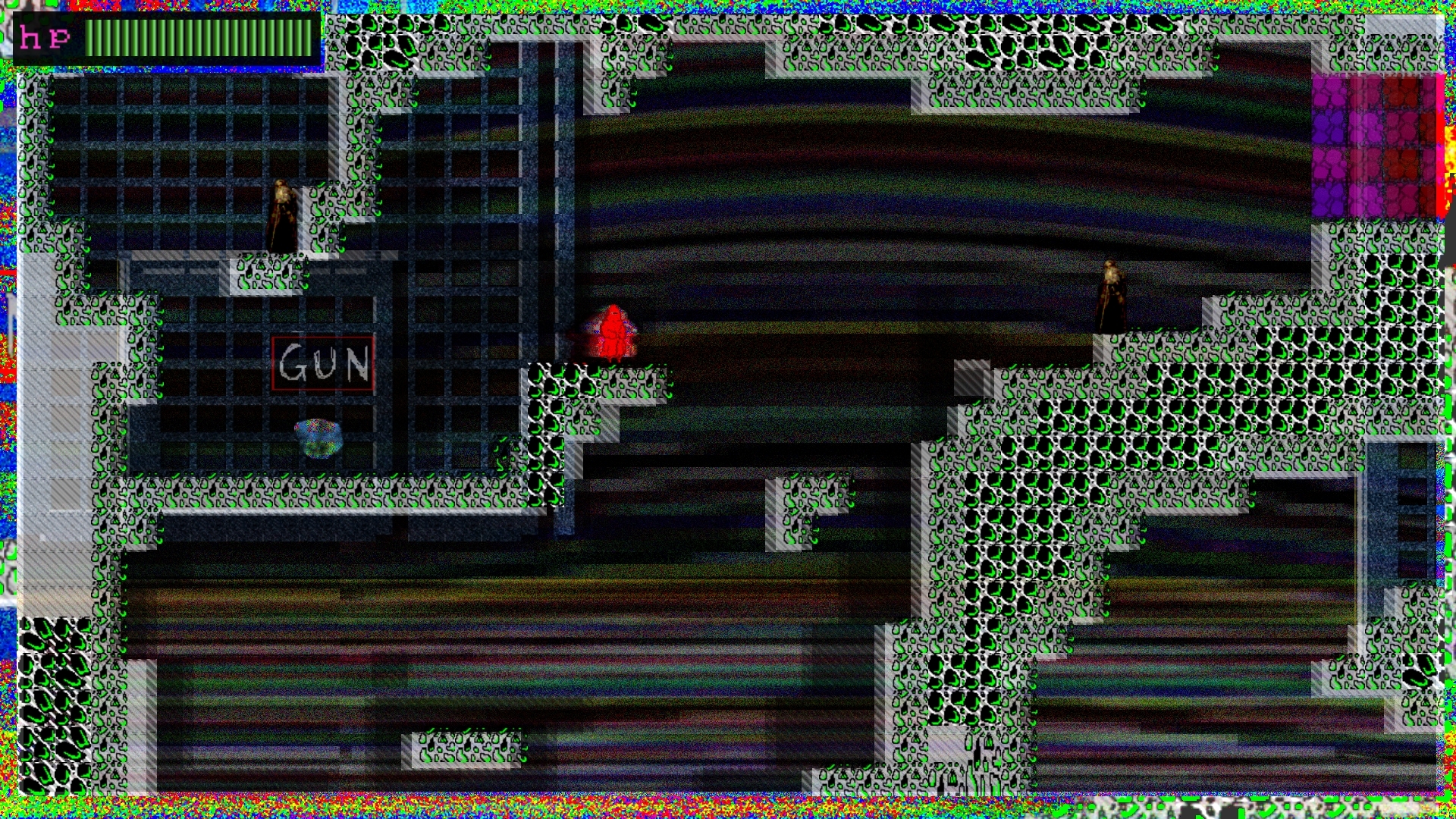

The most ambitious of these is Caves of Al Dajjal, a Metroid-style adventure platformer. Caves is King-Spooner's baby: its prototype was prominently featured in Dujanah's Kickstarter, and there's easily an hour's worth of dungeon to explore. Unfortunately, Caves is badly out of place. Unlike the rest of Dujanah, it emphasizes unforgiving platforming and perfect command of the (non-customizable) control scheme. It's aping Cave Story, but lacks the precise controls that made that game work. The floaty jumps and hazy, indistinct visuals that reinforce Dujanah's themes elsewhere mean that this game-within-a-game is so frustrating that it overwhelms any meaning it might be trying to convey. Thankfully, completing Caves of Al Dajjal isn't necessary to finish the game, but there it sits, an inert lump in the middle of Dujanah's strongest moments.

Dujanah isn't a straightforward game. It's a delirious fugue state of mourning; what happens isn't clear or consistent, what's real isn't always obvious. It isn't flawless, either: breaking the fourth wall is an occasional distraction, and Caves of Al Dajjal is badly out of place. Despite this, its unconventional narrative, a string of thematically linked images, succeeds at bringing the player into Dujanah's life as she comes to terms with her powerlessness in the face of loss. Dujanah hurts. Her pain and anger are felt in a way many clearer, less ambiguous games can't match.

This journey through a dreamscape of loss and absolution is unique, if a bit uneven at times.