The end of Steam: imagining the future of how we buy games

What would PC gaming look like if Steam were history?

Over the past few years, Steam has added refunds, tried paid mods (and failed), integrated virtual reality tracking technology, and now will let anyone publish games for a fee. If you’d told me all this ten years ago I’d have laughed, just as I probably wouldn’t have believed you in the late 1990s if you told me I had already purchased more boxed games than I was ever going to buy for the rest of my life.

I can’t predict the details of exactly how Steam or any other PC gaming service will change, but I can safely say that they will change. With that in mind, the question becomes: What do we want that change to be? What general possibilities can we imagine, and will they make our experience better or worse?

I’ve indulged in this hypothesizing with input from a few games industry folks, borrowing their experience to imagine some possible futures: a mega-service run by a board of publishers, a consumer-friendly service run by a nonprofit, a totally decentralized service, and big moves by giants Amazon and Tencent. Here’s a glimpse at a few PC gaming galaxies far away from our own...

The end of Steam

If Steam disappeared, everything would probably stay pretty much the same.

If we deposed Valve as the leader of PC game distribution, what could replace Steam? In one universe, the biggest game companies band together to build a super platform, much like how Hulu formed out of collaboration among Disney, Fox, Comcast, and Time-Warner. And so Steam merges with Origin merges with uPlay. Such a multi-headed corporate monster seems unlikely, but it's one approach to rebuilding a central platform.

Meanwhile, in a more pleasant universe, I can imagine a nonprofit with the simple goal of being the best possible marketplace for everyone, taking a cut from sales only to improve its service, and opening up APIs to the community so we can build our own clients. It’s an optimistic vision that initially excited me, but, as it turns out, might be just a little too optimistic.

I told Glass Bottom Games founder Megan Fox about my plan yesterday, describing how I was brilliantly going to use peer-to-peer networking to solve the issue of server costs. Fox put the kibosh on that. How do you stop someone from injecting something malicious into their copy of, say, Call of Duty, and spreading it through this P2P network? Even great security can be broken, creating a ceaseless struggle to keep the platform safe and paywalls intact. (And anyhow, what I was describing struck Fox as awfully similar to itch.io.)

TinyBuild CEO Alex Nichiporchik knocked me down another peg, explaining how running their own online store came with “a ton of perks,” but was ultimately crushed under the weight of chargeback fraud. And then there’s the issue of getting the word out through advertising, and of course, making something worth using. “Your matchmaking APIs, social graphs, friend systems, everything needs to work together and [be] built by world-class designers,” he wrote.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

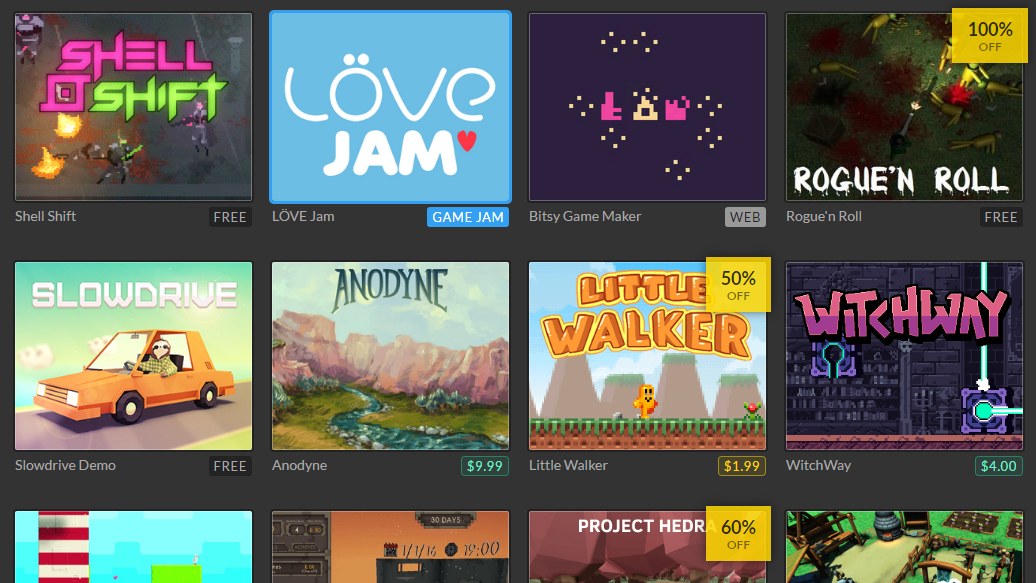

Given how great of a challenge it would be to rebuild a Steam-like service from scratch, I have to imagine that if Steam disappeared, everything would probably stay pretty much the same. The EAs and Ubisofts would keep running their own platforms, with one of the emerging as the victor and filling Steam's role, and GOG and itch.io would continue to serve independent creators. So from here on out, let’s strip away the need to be practical and get more creative.

Cryptocurrency and global platforms

Obviously there'd need to be super strong cryptography to protect against theft, but it's totally possible!

Black Ice developer Garrett Cooper had a fun idea, and while it would face all the challenges of the nonprofit organization I already described, it'd do so in a much more interesting way. A nonprofit would be nice, suggested Cooper, “But what if we went with a model based on cryptocurrency?”

“Structuring game distribution like Bitcoin could be super interesting!” wrote Cooper. “Obviously there'd need to be super strong cryptography to protect against theft, but it's totally possible! You wouldn't even necessarily need a central distribution server, each player connecting through the client could donate some bandwidth and CPU cycles to running the system. And a developer would just need a private key to access and update their game, similar to how bitcoin wallets work. Hell, you could even reward users for positive interactions on the system (like reviewing and tagging a game) with a cryptocurrency built into the system."

Cooper suggests a completely decentralized system, in which developers handle their own support (as he points out, not that much different than Steam) and which rewards curators and volunteers who work on the platform with cryptocurrency. It’s somewhat fantastical—and Bitcoin has had a few problems here and there—but Cooper’s idea is an imaginative take on what could happen.

What’s the leading game product in Africa?

For more possibilities, I spoke to someone who has a lot of experience in game distribution platforms: Larry Kuperman, director of business development at Night Dive, and former business development manager for one-time Steam competitor Impulse.

Kuperman thinks the two main threats to Steam right now are Amazon and Tencent. Both companies have egregious amounts of money to throw at the problem, and both are making moves. Amazon now owns a game engine (which Star Citizen is using), has a game studio, and recently bought Twitch—which it’s using to sell games. Tencent is a massive Chinese company that may be thinking about worldwide expansion.

I can’t say it’s a future I’m particularly excited for, but Kuperman and I did discuss some fun hypotheticals. For instance, imagine a truly global platform which deals heavily in digital importing and exporting. That is to say, a version of Steam which doesn’t just include translated versions of its storefront, but actively seeks to bring the biggest Chinese games to English-speaking audiences, and the biggest English games to Chinese audiences, and likewise for every other region, language, and culture.

“One of the things that I see about really being positive about Tencent is that we might get past that Western bias,” said Kuperman. “If you stop and you think about it, you can throw rocks from Steam’s office to Amazon’s office in Seattle, right? Now I’m not saying that Jeff Bezos and Gabe [Newell] are making the decisions on which games to promote and which games not to, but there’s a certain amount of perspective bias.”

“What’s the leading game product in Africa?” Kuperman asked me. He waited a beat before saying that he doesn't know, either, but suspects it would be wise for anyone interested in the games business to find out.

Will DRM end?

Valve sprung paid mods on everyone like a clown popping out of a jack-in-the-box, and that awful clown face laughed in what many saw as the spirit of modding—free, collaborative, community-focused. And so it failed, at least in its original form. Is there a better way?

One possibility: Take the money from game sales. After all, mods increase the value of a game. Publishers could deposit some percentage of a game’s revenue into a fund—let’s say 5%—and distribute it monthly according to how many people are using each mod. There’d need to be some minimum popularity requirement so that no one is getting a check for $0.001, the option for multiple authors to receive a cut, and strict anti-fraud measures.

As for what we have now, Kuperman’s says he’s “agnostic” on DRM, which is “less of an issue now than it was years ago.” Just five or six years ago, I wouldn’t have expected anyone with the term ‘business development’ in their title to shrug off DRM, but as GOG attracts more and more developers, the fear of a piracy free-for-all seems to be diminishing.

“If I talked about the ideal platform, it would allow me to reach a large audience but have control over how I reach that audience,” said Kuperman. “So, let me put my game on sale when I want it to be on sale."

Despite our various gripes, Kuperman says we're living in a "golden age" of gaming, contrasting today's huge variety of platforms to his days working in retail game sales, which gave far fewer opportunities to indies and required answering to people who didn’t know anything about games. If this is a golden age, then, maybe we shouldn’t want a sharp delineation between the present and future, as there was with the transition from physical sales to digital sales.

For a vision slightly less bold than cryptocurrency or a global Tencent, one can imagine a mix of Steam and GOG, where developers have the option to sell protected or DRM-free games. This could happen on a new platform, or an existing one—though we know GOG wouldn't go for it, so that only leaves Steam, alive and well as it is now, to change.

The idea of Steam introducing a DRM-free option might have seemed outlandish in the past, but GOG has made real headway. As for why any developer would intentionally forego Steam’s DRM protections, perhaps Valve would offer extra promotion and take a smaller cut of the revenue for DRM-free games. While Valve cedes some control—currently it only licenses us games—it picks up some goodwill without shutting out companies like Activision who'd never go for a mandatory DRM-free service.

Of course, all of these hypothetical worlds are based on a big assumption: that the social and economic conditions present in the world today will remain roughly the same. And that creates certain expectations about who is likely to make games, and why they're made, and who profits from them. The world may be very different in 10 or 20 years, for better or for worse. For now, and when it comes to PC gaming, let’s simply hope that Gabe doesn’t have an evil twin who usurps his throne and focuses all of Valve's resources on trading cards.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.