How game sizes got so huge, and why they'll get even bigger

It's the textures above all, and nothing is going to stop them.

"Crunch," in modern parlance, is a period of unhealthy overwork during the lead up to a game's release. But in the not-too-distant past it could have also described the nature of the work itself: a crunching and culling of excess data, enough to squeeze the whole game onto a DVD or two and comfortably onto a 100GB (or smaller) hard drive.

Game sizes have always been limited by their delivery medium—Myst was famously made possible by the introduction of the CD-ROM drive—but in 2004, when dual-layer DVDs were introduced, it was already too late for the PC game shelves at retailers. Steam launched around the same time, and as broadband snaked further into the suburbs and beyond, no physical medium could keep up with downloading. Games were allowed to grow, and grow, constrained only by users' bandwidth and hard drive space. That's resulted in 100GB-plus games that wouldn't even fit on a Blu-ray disc, never mind a dual-layer DVD.

That's causing grief for players who don't have access to speedy internet connections, or who haven't recently upgraded their storage in a pricey SSD market. It's especially bad for those stuck with data caps, a maximum data allotment per month that, if exceeded, results in extra charges. Broadband Now has catalogued 210 internet service providers that impose data caps.

For PC gaming to get better for those with poor internet service, either games will have to get smaller (or at least stop growing), or our selection of ISPs will have to get better, providing quality, uncapped service to more customers. After speaking to a few game developers, I can say confidently that the former isn't going to happen. The upper limit of game sizes is only going to increase.

What's taking up all the space?

Audio contributes a great deal to file size, but it hasn't been the primary contributor to the growth of game sizes in general. The resolution (sample rate) of audio will depend on what sounds the developer is reproducing—Tripwire, for instance, uses 44kHz audio for weapon sounds, and 22kHz audio for speech—but that was already the case back when it released Red Orchestra: Ostfront 41-45, one of the first third-party games to release on Steam.

The use of 5.1 surround sound audio over mono or stereo audio has been one reason games are getting bigger, but the simple inclusion of more audio has probably had a greater effect. We expect voiced characters and high fidelity audio far more than we once did.

Video, on the other hand, has broadly increased in resolution—from 640x480 cutscenes way back when all the way up to 4K—which has notably increased its footprint on game sizes. Video can be heavily compressed, though. "1500x compression factors are not unheard of," says Stardock lead developer Nathan Hanish, pointing to the H.264 codec. So while high-quality audio and high-resolution video have helped bulk up games, they alone can't account for the leaps in size we've taken since 2000.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

One element does check all the boxes for exponential growth: textures.

One element does check all the boxes for exponential growth: textures. Like video, textures are increasing in resolution, except unlike video they aren't fond of being compressed. Images can be heavily compressed—as with jpgs—but artifacting would be noticable. And regarding Hanish's specific work on Stardock games, "[DirectDraw Surface] images have to use a GPU friendly memory layout," he writes. "They only use local block compression, and thus yield at best an 8-to-1 compression."

On top of that, textures are also growing in complexity. "In 2005 you had a texture, just a texture, which is what later people would call a diffuse texture, but it's just a texture," says Tripwire Interactive president John Gibson. "And then in the next generation, you have a diffuse texture, a normal map texture, and usually a specular—like a 'shininess' texture. So not only are you using a higher-resolution texture, because video card memory increased, and computer memory increased, but you also have three of them for every object."

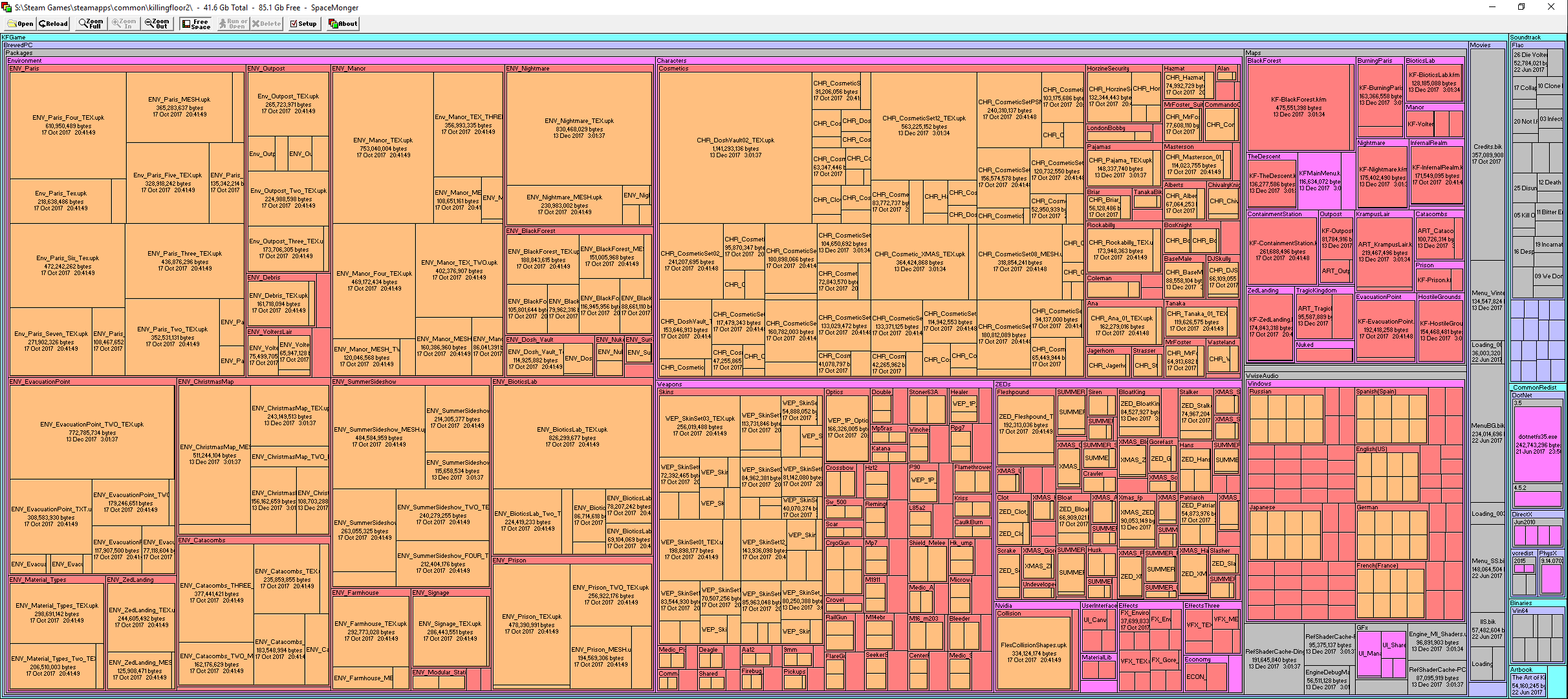

Those objects—their meshes—are increasingly complex, too. A breakdown of Tripwire's games tells the story. In the mid-2000s, Red Orchestra 1 released at 2.6GB, which players thought was awfully big at the time. ("People would complain if we did a 100 megabyte patch," says Gibson.) Sound only accounted for 327MB of that release, and environmental meshes and textures weighed in at 1.4GB. Jump to Killing Floor 2, which released last year, and sound now accounts for 1.1GB of the whole. Environmental meshes and textures? 17.4GB.

"One of the quickest ways to make your game look better is to up the texture resolution," says Gibson. "Content will be authored at a very high resolution no matter what game you're making, and then you res it down to what will fit into memory. And as memory expands, people keep doing higher and higher resolution textures."

If you want something to blame, look to the mossy rocks, the peeling wallpaper, and the freckled faces.

The same trend can be seen in Stardock games from 2003 to the present, beginning with Galactic Civilization 1: Ultimate Edition, which was largely bulked up by Bink video files. In 2011's Galactic Civilization 2: Ultimate Edition, textures grew to snag about 15 percent of the total filesize on their own. In 2015, Galactic Civilization 3's textures grabbed another five percent to become 20 percent of the total size. And in Stardock's latest, Ashes of the Singularity: Escalation, textures account for 60 percent of the total file size, says Hanish.

Textures aren't the only culprit, of course. Some games have no 'textures' in the 3D rendering sense in the first place, and some are very heavy on high-res video and can attribute the bulk of their size to that. Everything else has been growing, too, including executables, geometry, redistributables, and so on. But "textures have grown exponentially and represent (by far) the largest absolute and proportional area of growth—at least for Stardock products," writes Hanish, so if you want something to blame, look to the mossy rocks, the peeling wallpaper, and the freckled faces.

Why are some games so much bigger than others?

Game sizes can be confusing. Why, for instance, are The Witcher 3 and Rainbow Six: Siege both 50GB despite one being an open world RPG and the other being a multiplayer shooter? Such comparisons indicate that the 'scope' or 'size' of a game, as we perceive it in terms of 'a world' or 'hours of story,' has little bearing on install size. Vast plains built of terrain geometry and repeating grass textures appear bigger in our heads than they actually are on disk, while a complex gun model that's physically small in-game may weigh more than we know.

NBA2K17 is 66GB, for instance, a hefty install size. Why would a game that takes place within NBA arenas be bigger than the entire world of The Witcher 3? For one thing, every player from every team is modeled and textured to a high degree of fidelity, whereas The Witcher 3 probably contains far fewer unique bodies and faces. And as Hanish pointed out when I brought up the topic, there's likely a heap of motion-captured animation data in NBA2K17.

There are other questions. How much video is included? And audio? And is it compressed? Titanfall was a big game after install—48GB—because it included uncompressed audio to lessen CPU load. We can assume that from Respawn's point of view, accommodating dual-core CPUs would increase the number of satisfied customers more than a smaller install would have.

Why not just compress everything?

Why is it that people always seem to be finding unused assets in games? Cut content often makes it into full releases simply because of how complex game development is. Forsyth mentions, for instance, that artists may bundle a texture with a model for another artist to work with, and that texture might make it into the game even though it's duplicated elsewhere.

And as games get more and more complex, and take longer and longer to develop, the probablility increases that unused data will make the cut.

"Because these projects are so big, there are so many assets built up by so many people over a number of years, it can actually become very difficult to know which assets are or are not actually running in a game," says Hanish. "…So I imagine that, obviously not in any of our games, but in other people's games, there are probably a fair number of art assets that make it out into the distribution that aren't actually used anywhere."

(I'll take Hanish at his word that Stardock's games are free of excess data.)

That 48GB Titanfall install was 'only' a 21GB download, though, meaning it was heavily compressed. So why don't more games do that? An educated guess: it was only the fact that Titanfall's large install size was mostly audio that made it possible to compress it to 21GB in the first place.

It's those pesky textures again. We've established that textures have been the biggest contributor to the overall increase of game sizes, and as Hanish said, textures can't be too heavily compressed. Unfortunately, they also can't be heavily compressed during download and then transcoded at install time, because that process "is extremely CPU and memory intensive and must really be performed in the studio," says Hanish (adding later that "some flavors of dds are much more intense than others to transcode").

That's not to say that compression doesn't occur (Steam itself compresses games and decompresses them after download, Gibson tells me). Nor does it mean developers don't take pains to decrease download sizes. It just isn't practical for every type of data, and isn't nearly as vital as it used to be.

Oculus VR coder Tom Forsyth, who previously worked on games for the PC, Dreamcast, and Xbox, recalls the crunching required to squeeze games onto discs back in the late '90s and early 2000s. He built utilities to compare compressed and uncompressed textures, to determine which looked acceptable in their compressed state and which had to be left uncompressed. He also hunted down duplicate textures and other unnecessary bits and pieces. While working on StarTopia, Forsyth even invented his own audio compression format to solve a problem with the music—with a week before shipping. Solving these problems, sometimes at the last minute, was necessary, as "you either fit on the disc or you didn't."

The same space-saving efforts happen today (Hanish described more-or-less precisely the same processes), but because an extra 200MB no longer blocks a release, and Steam won't take a bigger cut for a bigger game, there's far less incentive now to set a hard size limit during development. If shaving off a gig means a delay, or means resources can't be allocated to pressing bug fixes and improvements, it probably isn't going to happen.

You could spend years on compressing this stuff. But nobody has the time.

Tom Forsyth

"It's an infinite rabbit-hole," writes Forsyth. "You could spend years on compressing this stuff. But nobody has the time. Especially as you only really appreciate the problem once you're close to shipping. So do you delay shipping by a month to reduce the download size by 20 percent? That's a terrible trade-off—nobody would do that."

No developer I've spoken to denies that, with enough time and work, bytes can probably be taken off of any final build—at least until you get to some theoretical lower limit. But does cutting 50MB matter for a 30GB release? That's especially questionable when, as Gibson points out, the game is probably going to grow after release anyway. Free Killing Floor 2 updates have added new maps, modes, skins, items, and so on since its release.

2D games and intentionally low-poly, flatly-textured games will continue keeping the low bar low. Stardew Valley, for instance, is only a 462MB download. But Forza Motorsport 7 is a 96.5GB download, and there's no sign that the upper bar is going to stop rising.

"The moral of the story is: buy stock in ISPs and hard drive companies," jokes Gibson. And that's how it is. As our hardware gets better, developers are going to want to use more and more of our memory for higher quality audio, video, geometry, and textures—which means bigger games. We have little choice but to rely on our internet service providers to make fast, uncapped connections affordable. Unfortunately, ISPs, many of which pushed to repeal Net Neutrality regulations in the US, are not great allies. But at least our big, big games are going to look shiny (or specular) as hell.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.