The psychological horror of In Sound Mind feels years out of date

The kickable shopping cart made a noble effort, though.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

One of the first words you hear in In Sound Mind, growled with malice as the camera sweeps back across a cityscape flooded with oil-slick water, is “curiosity.” It’s something the game is confident you’ll feel. Aren’t you curious about how you’ve woken without memories in this nightmarish apartment building? Don’t you want to find out what’s up with the talking cat, or the hostile entity who refuses to stop bullying you over the phone?

Sadly, my answer was never more emphatic than “I guess?” In Sound Mind can’t quite manage to generate that curiosity. Instead, as I muddled along as amnesiac psychiatrist Desmond Wales to piece together a series of psychological terrors and tragedies, I couldn’t shake the feeling I was playing the same kind of horror game I’ve been playing for a decade or more. Once again, I was trailing the long march of games in the lineage of Layers of Fear, Amnesia, and Condemned, to the same destination: the same grungy hallways, the same scrounging around for flashlight batteries, the same obligatory fascination with insanity. In Sound Mind colors well within the lines.

There are things to like though, many of them visual. The imagery as Desmond’s apartment contorts itself into a surreal mindscape can be genuinely arresting. As you wander beneath whale carcasses and phantom lighthouses, titanic cassette tapes loom over the horizon, their tape reels spinning while audio logs play.

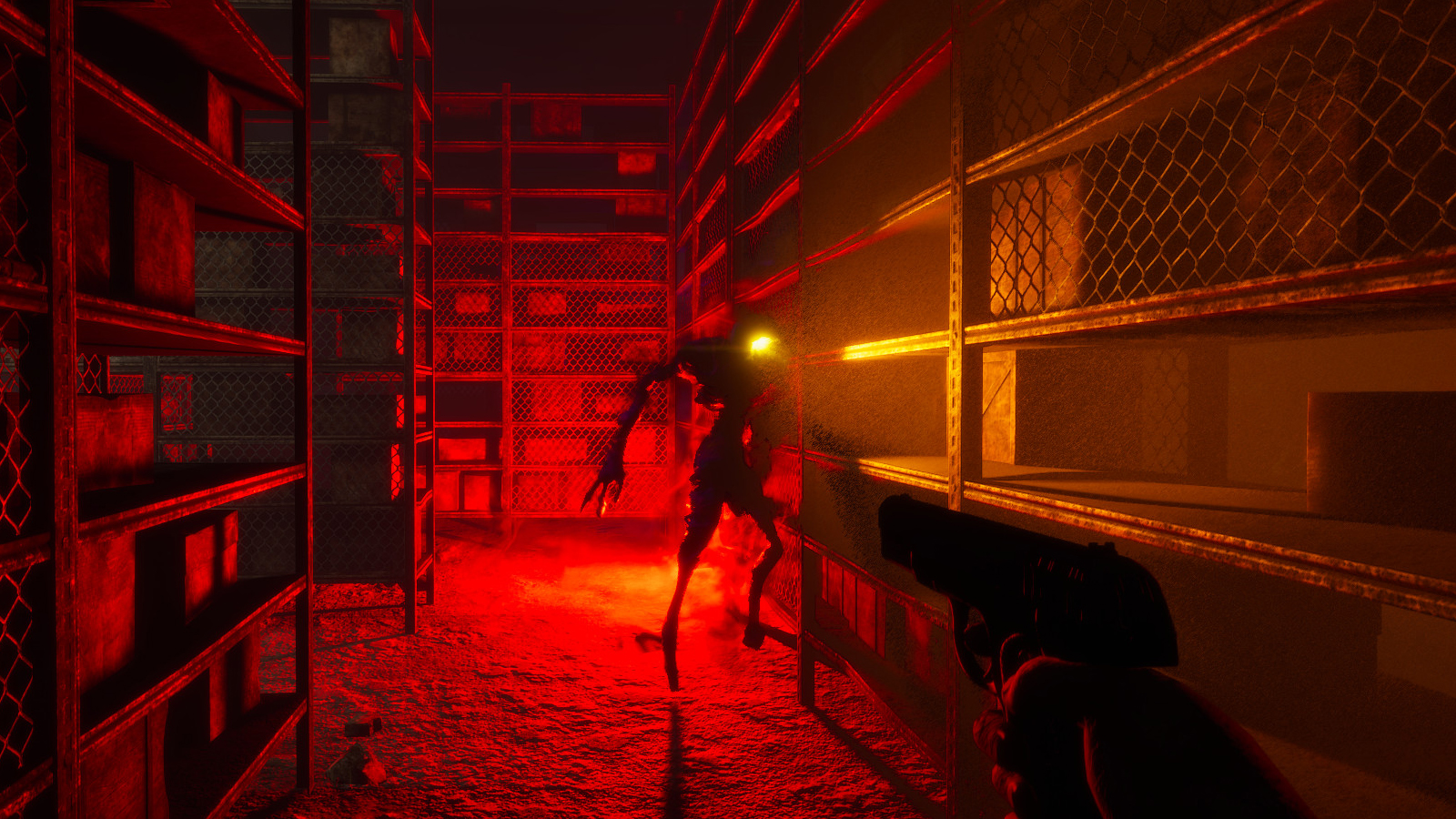

The pools of toxic pharmaceutical sludge are lovelier than you’d expect, and I loved the inky, distorted silhouette of the basic enemies, despite the stiff character animations. Mechanically, some interesting ideas present themselves, like a shard of glass that reveals hidden items behind you when you look into its reflection. There’s a shopping cart that’s more fun to kick than it has any reason to be.

And yes, you can pet the cat.

But otherwise, while it’s perfectly playable, In Sound Mind struggles to make any lasting impact. Its writing and vocal performances land somewhere between corny and melodramatic—although they provide one of the game’s main joys, as you can hang up on the antagonistic voice who calls you throughout the game at will. The puzzle designs are enjoyable enough, but it can be tedious having to fumble with an inventory you can only navigate with directional keys. Especially when I had to reenact a nonsense sales promotion, scanning items on a sequence of abandoned cash registers to match specific prices.

There’s a good amount of mandatory backtracking, often without the kinds of discoveries or revelations that make retreading the same areas feel justified. Instead, your main reward for exploring is the pharmaceutical pills which serve as character progression: collect three of the same type, and you get a stat boost.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

If I’m really disappointed by anything, it’s that In Sound Mind never felt particularly horrifying. There are plenty of little jumpscares and spooky thuds, occasional brief glimpses at lurking threats, but nothing that spiked the heart rate as much as I’d hoped. Maybe most damning is that its enemies, including each area’s boss, felt more inconvenient than scary.

It doesn’t help that when In Sound Mind tries to paint with psychology as part of its horror palette, some of its attempts dip from clumsy to tasteless. During a sequence in the nightmarish reflection of a shopping center, it was hard to ignore that the game was asking me to defeat a ghost by repeatedly exposing her to the trigger for her psychosis—essentially asking me to weaponize a woman’s own fatal psychological trauma against her to progress. It felt gross.

Ultimately, In Sound Mind is walking some well-worn paths—the horror equivalent of competently made comfort food. Trust me, though: when you find that shopping cart, give it a few boots from me. You’ll be glad you did.

Lincoln has been writing about games for 12 years—unless you include the essays about procedural storytelling in Dwarf Fortress he convinced his college professors to accept. Leveraging the brainworms from a youth spent in World of Warcraft to write for sites like Waypoint, Polygon, and Fanbyte, Lincoln spent three years freelancing for PC Gamer before joining on as a full-time News Writer in 2024, bringing an expertise in Caves of Qud bird diplomacy, getting sons killed in Crusader Kings, and hitting dinosaurs with hammers in Monster Hunter.