Crapshoot: The almost-great noir detective mess, Private Eye

We're rerunning Richard Cobbett's classic Crapshoot column, in which he rolled the dice and took a chance on obscure games—both good and bad.

From 2010 to 2014 Richard Cobbett wrote Crapshoot, a column about rolling the dice to bring random obscure games back into the light. This week, who's in the mood for something... noirishing?

The inevitable sound of smoky jazz echoes down the dark Los Angeles street. Somewhere, a man falls to the ground with an ice-pick in his neck. A damsel puts the finishing touches to her look of mock distress. A crucial clue is picked up off the floor and torn up by a genre-savvy plotter. And in his dark, cramped office, Philip Marlowe waits to be told the lie that'll pull him into the middle of it all.

Yep. It's time to head back to the golden age of detectives and take a look at a game that—while no classic by any stretch—deserves better than to languish in its current obscurity.

Proper detective games have always curiously been thin on the ground. Sure, there have been plenty of games where you play a detective, but that's not necessarily the same thing. Any old flatfoot can find a few hidden objects on a screen, or shove a bit of newspaper under a door to recover the key on the other side. To actually feel like a sleuth is to enter a world and be given the chance to investigate; to work out whodunnit instead of having to be told. Half the fun of watching detective fiction is trying to get one step ahead of Poirot, Sherlock Holmes, Jonathan Creek or whoever.

It's rare to see an actual game built around this rather than straight-up solving puzzles though, to the point that you usually have to head back to the 90s and games like Laura Bow to even get close to something resembling a case to pick apart with your, how you say, leeetle grey cells. Sure, a few have tried, like Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective and the Phoenix Wright series, but nowhere near enough.

(At a pinch, you could also add Fog, but that's less of a game than the answer to the question 'if a multiplayer adventure is released and nobody plays it because it's shit, does it actually exist?")

Philip Marlowe: Private Eye... or Private Eye: Philip Marlowe, the logo makes it a bit tough to tell which way round the words go... is one of the few that tried. It didn't make much of a mark, ultimately ending up slumming it with Noir and The Dame Was Loaded instead of joining Tex Murphy and Discworld Noir in glory—but that doesn't mean it didn't do anything worth remembering before it disappeared.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

Marlowe was always my favourite of the classic pulp detectives: the iconic PI with a sharp tongue, hard-boiled exterior, and noble heart that both separates him from the far more cynical world around him and ensures he's constantly ground down by it. They're traits shared by others of his era, not to mention subsequently picked up by everyone from Tex Murphy to Harry Dresden, but you just can't beat the original. Sam Spade? Nah. Bit of a bore, especially when played by Bogart.

Unfortunately, if you're a fan of the character, you won't find much mystery in Private Eye. It's based on the novel The Little Sister in much the same way that a photocopy is based on an original sheet of paper, with precious little you don't already know. There's the option to play an alternate version of the story with a different criminal and a few minor changes here and there, but the majority of the investigation remains the same. If you haven't read the original on the other hand... well... prepare for confusion. As great as Chandler was, his actual stories could be a bit of a mess. Most famously, when a movie was being made of Marlowe's first case, The Big Sleep, the makers called Chandler to ask "Uh... who killed this guy near the start?" only for the author to realise he hadn't got the faintest clue.

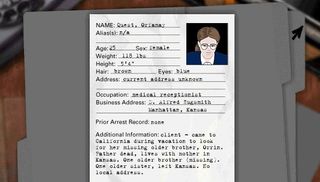

The Little Sister doesn't have anything like that, but it does seriously pile on the plot threads. In the book, this doesn't matter—it's Marlowe's job to solve it, and you're mostly there for his attitude and to see what happens. When you're the one in charge, simply staring at a pile of names like "Orfamay Quest" (no relation to Johnny Quest or the Quest for the Holy Grail) quickly gets confusing, and the story moves from simply trying to track down Orfamay's missing brother to a whole heap of other trouble, including icepick murders, false identities, and intrigue involving Hollywood starlets.

Thank goodness notepads are so cheap. You really need one here.

Investigating the case is an unusual experience, though—a mix of adventure (pointing and clicking), interactive movie (it's a very pathed game) and radio play (there's a lot of talking) that only really works because of the extra little elements scattered in. My favourite, and one I don't think has been done anywhere else, is how the game handles crime scenes. Marlowe's method of investigation has a tendency to dump him on the wrong side of the law, not always for particularly smart reasons. In keeping with this, you're quite welcome to walk into a crime scene, pull an icepick from a corpse's neck and stash it in your pocket for later. After all, you need evidence, right? However, you also have to factor in that when the police finally decide to check out your office, they're not going to be impressed if they find a cupboard full of bleeding murder weapons and other souvenirs you pinched. And they're certainly not above just arresting Marlowe for the crime and declaring it a three-day weekend.

Does this have much impact on the game? No, not really. It's a great idea though, both making you think a little more carefully about how you handle each situation and ramping up the danger. Similar scenes include only having a limited amount of time to raid a room before the police show up, and hoping you grabbed everything, and simple decisions like whether or not to investigate before interrogating a suspect or vice versa. It also leads to the hilarious image of Marlowe casually pulling an icepick out of a corpse's neck, considering it, then going "Nah" and stabbing it right back in.

Adventure gaming still desperately needs ideas like that, and while Private Eye is too tied to its source material to make the most of them, they're probably why I look back on it so fondly. It's a shame that there wasn't a follow-up with a completely fresh story, although looking at the general quality of storytelling here, you can see why—it's a great demo of how words that would be fine in a novel written in the 1950s don't necessarily shine in an interactive game designed for 1997. Modernising classic stories is tough, even if you're not planning to drag them gloriously into the modern day.

What it lacks in spark though, it more than makes up for in atmosphere—the music, the location design, the use of cel-shaded characters that fit into them instead of blotchy FMV characters filmed in front of a bluescreen—and that's honestly as much of noir's appeal as the stories the genre lets unfold. There are better noir games, like the aforementioned Tex Murphy series (and The Pandora Directive especially) and Discworld Noir, but few that make it so satisfying to slip into a pair of gumshoes and snark at a prissy dame from Kansas whose attitude really isn't worth a measly $20 a day plus expenses.

$40 a day? Perhaps. That whisky and detective-friendly dog-food's not going to buy itself...

Oddly, the age of the original story and its setting mean that while Private Eye has obviously dated, it manages to pull off the rare trick of feeling retro rather than ancient. If you're a Chandler fan, it's still worth checking out if you see it cheap anywhere (though it's not 64-bit compatible). If you've never read any? Maybe you should fix that. You'll find cheap compilations almost anywhere books are sold, and the pulpier they are, the better. Afterwards, you might not feel like jumping into this adventure specifically, but that's OK. Hit the second two Tex Murphy interactive movies and you'll still get all the noir you can handle, along with a couple more adventures with the guts to be different.

Sigh. How I wish I'd been able to say "LA Noire" instead. How that disappointment still burns...

Most Popular