Lawyers explain why Campo Santo's takedown of PewDiePie's video is legal

Game publishers can send DMCA notices to Let's Players for almost any reason.

Back in February, the most popular YouTuber in the world posted an anti-Semitic stunt. Felix 'PewDiePie' Kjellberg defended his video, calling it a commentary on "how crazy the modern world is," though after more anti-Semitic imagery in PewDiePie videos came to light, Disney-owned Maker Studios cut ties with the YouTube star.

The legality of Disney terminating its relationship with PewDiePie was probably embedded in whatever contract the parties signed—'moral clauses' are common for entertainers and athletes. Today, however, we have a more unusual situation. PewDiePie's casual use of the n-word during a PUBG stream over the weekend prompted Firewatch creator Campo Santo to issue a DMCA takedown notice on PewDiePie's Firewatch videos. Can a publisher who objects to a certain YouTuber's character legally target that person with copyright claims for that reason alone?

The short answer is: yes.

DMCA notices are common on YouTube—Nintendo is notorious for making copyright claims against videos of its games—but aren't usually targeted at a specific person for a reason unrelated to the video itself. Campo Santo had not publicly taken issue with PewDiePie's Firewatch video prior to his behavior over the weekend. Yet nothing prevents it from doing so now.

What does the DMCA mean for YouTubers?

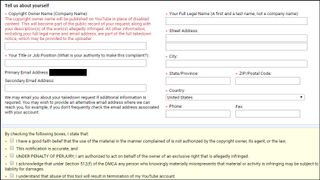

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act is a United States law with a broad scope, but the relevant section here is how it protects sites like YouTube, and what YouTube must do to receive that protection. Under the DMCA, YouTube and other 'online service providers' are not liable for copyright infringement committed by their users, but only if they meet certain requirements. One requirement is that "the service provider responds expeditiously to remove, or disable access to" infringing material at the request of the copyright holder.

When a DMCA notice is submitted, YouTube doesn't make legal judgments itself. If someone claims that your video infringes on their copyright, it's up to you to send a counter notification if you don't think it does. The notifier then has 10 business days to seek a court order. And you probably don't want to go to court over it.

If a license doesn't say 'non-revocable,' you can revoke it anytime you want.

Ryan Morrison

It's true that in the official Firewatch FAQ, Campo Santo gives players a blanket license to stream and monetize videos of Firewatch. But that wouldn't help a Firewatch Let's Player in court. "If a license doesn't say 'non-revocable,' you can revoke it anytime you want," says Ryan Morrison, founding partner at law firm Morrison & Lee LLP.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

Morrison has backup on that. "Publishers can revoke the license for any reason in their sole and absolute discretion, and there is nothing in the DMCA that requires consistent enforcement on the part of the IP holder," attorney Bryce Blum of ESG Law tells me in an email. "Arguing against a takedown request by saying other, similar content isn't targeted is like telling a cop that you shouldn't be busted for speeding because lots of people speed without getting a ticket."

Attorney Michael Lee, the other founding partner at Morrison & Lee LLP, also thinks Campo Santo is on sure footing. "A person can do and say whatever they want but it is the copyright owner's decision whether to shut that down," Lee told Rolling Stone. "Unfortunately, the DMCA has been used to stop criticism and negative comments about the underlying work but technically this is allowable under the DMCA."

If the DMCA can be used to silence criticism—as critic Jim Sterling could tell you all about—then it does seem unlikely that some other reason for issuing a takedown notice, such as not wanting to be associated with a racial slur, would violate DMCA rules.

If that's the case, can takedown notices be made for absolutely any reason? Campo Santo is only revoking the license for one YouTuber on the basis of behavior, but one can imagine hypothetical scenarios in which licensing is revoked in a discriminatory way—for instance, if a game publisher only sent DMCA notices to people of one ethnicity. Would that be legal?

"That's a more complicated question," says Morrison, but he tells me that 'slippery slope' arguments along these lines are "poppycock." Someone who says the n-word on a livestream is not a protected class, and so anti-discrimination laws do not apply. If a developer were to intentionally target only YouTubers of a certain race or religion, however, then there might be a case.

But in general, a YouTuber's only defense against DMCA claims is preemptive, says Morrison: getting contracts with publishers. Though even then they'd probably have to abide by a moral clause and refrain from saying the n-word on livestreams. For PewDiePie, if he really wanted to get that Firewatch video back up, his only defense would be fair use.

Are Let's Plays protected by fair use?

Because YouTube plays it safe to comply with the DMCA, the automated system can be abused—for instance, by someone sending notices for material they don't own. But even if the accuser does hold the copyright for material being infringed upon, the infringing party may be able to defend their infringement as "fair use."

This is where things get murkier. In the United States, "fair use is any copying of copyrighted material done for a limited and 'transformative' purpose, such as to comment upon, criticize, or parody a copyrighted work," according to Stanford University Libraries. So you're allowed to use bits and pieces of copyrighted material without permission if you're reporting on it, or criticizing it, or making fun of it—this is something we do every day when we include screenshots of games with our news stories and reviews.

Videogames are a somewhat special category of media when it comes to fair use. It is clear to film critics that showing 45 minutes of a 90 minute film, even for the sake of a critique, would not fly. Book reviewers may quote short passages, but would never reprint a 40-page chapter without permission and hope to be protected by fair use law. But because a video of someone playing a game is not the same as actually playing it (though this isn't a legal defense), and because it's seen as beneficial to publishers—free word-of-mouth marketing—gamers have been given exceptional leeway. There are streaming and video sharing capabilities built into our platforms (eg, Nvidia Shadowplay), something you'd never see in, say, a Blu-ray player. Livestreams and Let's Plays are part of modern videogame culture, and because of the symbiotic relationship between game publishers and 'content creators,' some of whom provide what amounts to free marketing, a huge number of potentially infringing videos go unchallenged.

If a strategy guide full of screenshots isn't transformative enough to count as fair use, are Let's Plays?

When they are challenged, your average YouTuber doesn't have the money to go to court, so commentary on the issue is largely hypothetical. One of the few examples of a game-related fair use case I could find, Midway v Publications International, well predates Let's Plays. Back in 1994, Midway sued Publications International for copyright and trademark infringement in its "unauthorized" Mortal Kombat strategy guide. Publications International moved to dismiss the suit on the basis of fair use, but was denied.

If a strategy guide full of screenshots isn't transformative enough to count as fair use, are Let's Plays? Maybe. But even if they were, that isn't the only quality a judge would consider. As stated in the Copyright Act of 1976 and explained by Stanford, there are four primary factors used when determining whether or not something is fair use: the "purpose and character" of the use, whether the copyrighted work is published or unpublished, the amount of the copyrighted work used, and the "effect of the use upon the potential market."

In 'Video Games, Fair Use And The Internet: The Plight Of The Let's Play' from Vol. 2015 Issue 1 of The University of Illinois Journal of Law, Technology, & Policy, Ivan O. Taylor Jr. examines three gaming videos according to all four criteria and concludes that Let's Plays "could very well fall under the protection of the fair use doctrine."

Morrsion, however, thinks it's unlikely. "I'd be happy to argue it, I'd be the first one to argue it," he says, but under the "current case laws" he doubts he'd win. Blum is also doubtful.

"This is a tough, open legal question," writes Blum. "The key factor for evaluating potential fair use is whether the creator has done something transformative to the original work. I think Let's Play videos seldom, if ever, meet that standard. At the end of the day, it's just someone playing the game within the exact confines set forth by the publisher and adding their commentary over the top."

In legal limbo

Because fair use law is case-by-case—"nothing is set in stone," says Morrison—there's no saying for sure whether PewDiePie or any other YouTuber could successfully claim fair use in regards to any specific Let's Play. We can make educated guesses, but unless a judge rules on PewDiePie's Firewatch video, the point is moot. And what would it cost to get a judge to rule on the case?

"Well over six figures," says Morrison. "So it's not something for indie developers or small streamers to rely on at all." PewDiePie might have the resources to take on Campo Santo, then, but there's a good chance he'd lose.

Let's Plays are allowed to exist solely because copyright holders allow them to.

To sum up, without a contract, any permission a game publisher gives to streamers and YouTubers is revocable at any time for (almost) any reason. With a contract, you'd still have a 'moral clause' that probably kicks in as soon as you say the n-word on a livestream. And while you can defend copyright infringement on the basis of fair use, you'd need to mount this defense for each individual video at great cost, and in the case of Let's Plays, two attorneys are doubtful the defense would hold up.

The situation with PewDiePie (if we ignore how fantastically wealthy he is as the most popular YouTuber) highlights the fragility of a YouTuber's livelihood. While state laws exist to prevent blacklisting in employment—that is, actively preventing someone from getting a job—YouTubers don't typically have any employment relationship with the publishers whose games they post videos of. While many publishers choose to allow Let's Plays, there's nothing stopping them from getting together as a group and taking down all of a YouTuber's infringing videos, and they don't have to give a reason. Let's Plays are allowed to exist solely because copyright holders allow them to, and they're free to pick and choose which ones they allow.

YouTubers aren't typically employed by YouTube, either, so whether or not they can monetize videos in the first place is entirely up to YouTube and its advertising partners. Even if they play by all the copyright rules, then, their channels can still go from profitable to nothing overnight. It's no wonder Jim Sterling, who earns money through multiple YouTube shows, is furious at bigger YouTubers for tugging at all these loose threads.

"It's because of shit like this that the 'adpocalypse' is happening where people's videos are being flagged as inappropriate for advertisers, because advertisers don't want anything to do with this shit," Sterling said of PewDiePie's incident in a video posted yesterday. "No matter how popular YouTube is, it's like professional wrestling. A lot of companies feel they're above it because it's for quote-on-quote 'rednecks,' so they don't pump money into a primetime slot. Then again, even WWE knows not to start dropping racial slurs in the middle of its broadcasts. At least now it does."

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.

Most Popular