Richard Garriott on why "most game designers really just suck"

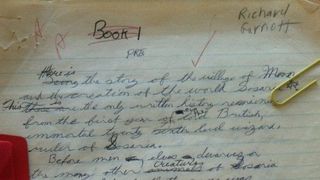

When Ultima creator Richard Garriott stopped by to show me Shroud of the Avatar, his new RPG which just met its $1M Kickstarter funding goal , he brought along some objects for show and tell. First, he produced a folder containing a stack of loose, lined paper—the first record of Ultima's world, featuring Sosaria, Lord British, and the evil Mondain. That should be in a museum, I thought.

"This is the founding document of Ultima, that predates even Ultima I," said Garriott. "This is 1976-ish, before I ever programmed a line of code. This is the story of the city of Moon and the world of Sosaria, with Lord British and the evil wizard Mondain, where I received a rare 'A' on something I did in English class, which I usually failed. This is before a personal computer even existed."

"I think most game designers really just suck"

Garriott went on to show me one of the first computer RPGs he—or anyone—ever made. It was programmed with holes in a roll of paper and, as it existed before displays, its output was an ASCII grid printed on paper. "So it's about 30 seconds per frame," said Garriott. "But it's basically doing tile graphics, back, even before there were graphics." Another one for the museum, someday.

The relics are a story on their own— Ultima is one of the most prolific and influential series ever—but Garriott was building to a point. After showing me Shroud of the Avatar, which he hopes meshes the best of classic RPGs with modern ideas, he moved on to talking about the classic principles of game design—the results of which he'd just been showing me—and what it means to be a great designer. He thinks the latter is rare in the industry.

"I've met virtually no one...who I think is close to as good a game designer as I am."

"You know, I go back to the day when I was the programmer, I was the artist, I was the text writer, etcetera," said Garriott. "Every artist we've ever hired ever is infinitely better at art than I ever was. I was never a good artist, or audio engineer, or composer. I was a pretty good programmer, but now all of our programmers are better than I am—but if I'd stayed in programming I could probably keep up.

"But other than a few exceptions, like Chris Roberts, I've met virtually no one in our industry who I think is close to as good a game designer as I am. I'm not saying that because I think I'm so brilliant. What I'm saying is, I think most game designers really just suck, and I think there's a reason why."

"It's really hard to go to school to be a good designer"

Chris Roberts, who worked with Garriott back when Origin Systems was producing both Ultima and Wing Commander, isn't Garriott's only exception—he also identified Will Wright and Peter Molyneux as examples of quality game designers. The majority, however, become designers because they lack other skills, according to Garriott's analysis.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

"If you like games, you eventually get to the point where you'd like to make one," said Garriott. "But if you had this magic art talent as a youth, you can refine your skills and show a portfolio and say, 'I'm a good artist, go hire me' If you're nerdy enough to hack into a computer, programming on your own, you can go to school and learn proper structure, make code samples and go 'Look, I'm a good programmer, hire me.'

"But if you're not a good artist and not a good programmer, but you still like games, you become a designer, if you follow me. You get into Q&A and often design. And the most valuable part of creating a game is the design, which the programmers are technically executing. And they'd be happy to just execute some of them. But in my mind, most artists and programmers are just as much of gamers as the designers, and I usually find in my history that the artists and programmers are, in fact, as good of designers as the designers. They're often better, because they understand the technology or the art.

"So we're leaning on a lot of designers who get that job because they're not qualified for the other jobs, rather than that they are really strongly qualified as a designer. It's really hard to go to school to be a good designer."

"Four-dimensional spreadsheets"

So how does a good game designer work? Garriott went on, explaining the design process which started back with that high school writing assignment. Using a "four-dimensional spreadsheet," Garriott says he records every character, location, and item in a game and blends them into the whole.

"OK, here's some magic items, have I distributed them around enough?" Garriott asked himself, miming his process. "How do they migrate across the story? What is the journey of that item through the game?"

"I think it's this discipline of how I break down storytelling—not just the story, but each region, each thread, each object, and I kind of do them all simultaneously. I kind of have a four-dimensional spreadsheet in this sense, even before there were 'spreadsheets,' that's how I broke them down in the beginning.

"I have the notebooks for Ultimas one through five—I would often get two or three binders, and one was the linear story, one was by character sheet, alphabetical, one was by town, and who was in each town, but it was the same information threaded thrice, because it helped go, 'Oh, I've put nobody in the city of Moon, who can I put over there? Or what part of the story can I shuffle over there?'"

"How can I really move the needle here?"

Garriott's love of detail in a world, its characters, and their backstories has been evident in the Ultima universe since the '80s. His method hasn't gone away—he's been working on Shroud of the Avatar's story and design on paper, just like he always has—and he thinks this skill, or something comparable, is lacked today, replaced by lazy rehashes of old ideas.

"And every designer that I work with—all throughout life—I think, frankly, is lazy," said Garriot, adding "to give you another zinger" in reference to my ribbing him earlier over his "game designers suck" line.

"But if you follow, they generally say, 'You know, I really like Medal of Honor, but I would have bigger weapons, or I would have more healing packs, or,' you know. They go to make one or two changes to a game they otherwise love versus really sit down and rethink, 'How can I really move the needle here?'

"You know, even if it's just a map. I really push my team on how to make a scenario map. How do you really think about the whole thing holistically, to go, 'yeah, it's fine to wander through and kill a few things and get a treasure at the end, but why? What's your motivation for being into it? What are the side stories? If you have these characters in there, what were their lives before they showed up on this map? If you didn't think of one, go back. Do it again. I want you to know it.'"

"I think there's really very few great game designers," he continued. "I think Chris Roberts is one of them, Will Wright's another, Peter Molyneux is another. They clearly exist, but on the whole, I think that the design talent in our industry is dramatically lower than we need, as an industry. It's a very hard skill to learn."

Strong words, especially coming from someone who created one of the most revered RPGs ever—as well as what might be the first computer RPG ever, as evidenced by the punched tape he presented—and whose experience is traceable to a 1976 high school English paper. If it can be said that PC gaming has "founders," Lord British is one of them.

To be fair, Garriott agreed when I asked if he thought some developers, such as BioWare, had been doing good work recently. His judgments are still very broad, but I inferred that, rather than condemning the entire industry, he was pointing out flaws he perceives in how design talent is assessed and promoted in specific parts of the industry. His ideal programmer, artist, designer combo still exists, especially among the current crop of indie developers, who I think retain the spirit of the early days Garriott is reminiscing about.

Garriott's new game, Shroud of the Avatar: Forsaken Virtues, has succeeded on Kickstarter with the promise that it's a "return to his fantasy RPG roots, hearkening back to his innovative early work."

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.

Most Popular