Watch Dogs 2 made San Francisco much more than just a playground

How an in-game app develops your relationship with Watch Dogs 2’s city.

For all of the money and effort invested into the open worlds where we spend so much time, it’s amazing how many ways we’re given to ignore their construction. Trained to ignore them, by the way the games they’re built around are designed. Maps are filled with icons containing vital missions and content and collectibles, so we set a course to the nearest desirable one and follow a line on the minimap until we reach our destinations. Turning on the secondary vision mode of Rocksteady’s Batman games, Detective Vision, is made so essential by its usefulness in identifying secrets and fighting baddies, that you can spend most of the game breezing by the sights of their graphic novel grandeur brought to virtual life. All for the sake of finding the next breakable wall.

While it might have disappointed some players and critics on its release, Watch Dogs actually found ways to emphasize the world its developers painstakingly crafted. Roots its successor paid off to remarkable effect two years later.

Beyond the cliched, problematic framing of Chicago’s criminal underbelly, and the hypocritical, unlikeable figure of protagonist Aiden Pearce, Watch Dogs genuinely seems to want to put a spotlight on the city it expects you to spend the next thirty hours roaming. This is a warmth that the central story belies. It attempts to do this in a few ways, the first being “Digital Trips”. They're fleshed-out minigames that allow you to bounce across Chicago on psychedelic flowers to rack up points, free districts of the city from the dystopic reign of robots, run down demons in a car with extendable buzzsaws, or take the controls of a literal Spider-Tank. They’re temporary changes of context, but it could be just enough for you to see Chicago as something more than a set of grey boxes hosting the site of Aiden’s revenge.

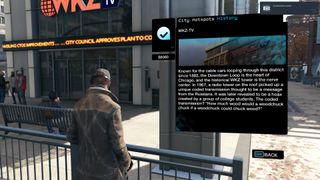

The second major method Watch Dogs uses to create positive connections with Chicago is a City Hotspot app on your in-game phone. Upon reaching certain Chicago landmarks, players can ‘check-in’ and read information about the location’s actual history. They can also donate gifts to other players who will follow in their footsteps, and if they continue to visit the location and check-in, rise to become the mayor of a given site (much like the Mayorship system in location service Foursquare).

The final, flawed way Watch Dogs attempts to showcase the life of Chicago is through its ‘profiler’ system. Tapping the Z key allows you to view all hackable devices in sight, as well as access the biographies, conversations, and even bank accounts of everyone around you. The one to four word vignettes comprising these biographical descriptions are, surprisingly, more damaging to empathy than enabling of it. You know just enough about this randomly-generated pedestrian to make a value judgement about them, but not enough to see them as a true individual.

Within Aiden’s dispassionate, swaggering stroll and scroll across his phone screen as you walk through the city, the people around you transform into data points. Prompts, just like the overwhelming flow of objective reminders popping onto your screen. You can drain the bank account of a struggling mother of four with a misplaced button press and not feel a thing.

Here, we see the tonal conflict at the heart of the game. Watch Dogs, the self-aware, silly, Chicago-set action game where hacking is a somewhat naughty superpower, and Watch Dogs as it was advertised: the ultimate loner hacker fantasy of the next generation, with all the grim ‘maturity’ and lack of empathy that supposedly entailed. The desire to entertain and even educate is present, but it’s buried in a game that already has too many things it wants the player to do.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

Enter Watch Dogs 2.

At first glance, in its attempt to get you to connect with the city of San Francisco, Watch Dogs 2 shares many of the methods (and potential weaknesses) of its predecessor. Scanning the map, you can still find information about city landmarks by hovering over their names. The profiler is still around, and the hacking systems of Watch Dogs 2 actually give you more ways to mess with NPCs than ever. However, these elements are tempered by the same spirit driving the game’s narrative—a focus on the whimsically personal.

The profiler is no longer an almighty, agency-stripping tool. Tapping the V key to use it strips the game world of color, reducing your screen to a grainy, blue-scaled void if you wish to look for collectibles or glimpse the lives of those around you. In doing so, it represents its data points as just that—data points. Small pieces of ‘actual’ people. It emphasizes that this ugly, omniscient view isn’t reality, or the summation of a given pedestrian. It's just a part of it. Despite the greater powers you wield, this simple change in context makes the player feel slightly more responsible for how they use or abuse the people around them.

This evolution in the depiction of the power of hacking, and the people, places, and communities that make up a city, is best seen in Watch Dogs 2’s replacement for the City Hotspots app: ScoutX.

As you travel across San Francisco, the phone of protagonist Marcus Holloway will vibrate. You’re next to a hotspot—it could be anything from the world-famous Golden Gate Bridge, to a street performer beneath a prominent pagoda in central San Francisco. A brief paragraph tells you more about the sight you’re interacting with. You hit the appropriate prompt and turn on your in-game camera, to find its automatic setting is a selfie mode. Toggling a series of gestures, you find a satisfactory angle and posture, and take the picture.

A set of celebratory chimes play as you gain ‘followers’, the game’s equivalent of experience points, and get one step closer to unlocking more unique, characterful selfie gestures for Marcus to use. This snapshot also produces a picture that your in-game companions will comment upon in the app.

It’s a compelling, self-contained loop, that educates, motivates through gameplay progression, and provides valuable personality while subtly causing you to become more familiar with this eccentric, vibrant city. In a demonstration of how far the narrative design and cohesion of the Watch Dogs series has come in a relatively short time, the app unites the player and Marcus, by turning both of you into tourists. His memories—his gallery of pictures—become yours as well. And once you begin to look at San Francisco through a lens of seeking the weird and photogenic, something magical happens.

Coming out of the profiler, you see a cool series of abstract lines drawn on the side of a building. You climb up to the site, pull out your phone, and find that...it’s not listed in the ScoutX directory. It’s cool. It might even exist in real life, but you won’t be rewarded for taking a picture of it. So, objective-oriented as you are, you leave—but the graffiti sticks in your head. Another in a string of landmarks you come to recognize across the virtual San Francisco. One not signposted by the game.

Passing by one day, you and Marcus stop to finally take that picture.

Welcome to San Francisco.