The complete history of Fallout

Who knew the end of the world could be so full of life?

This article was originally published in issue 186 of Retro Gamer. Consider subscribing to this award-winning magazine. Since this was published before the release of Fallout 76, we've added a few tweaks to the conclusion for ease of reading.

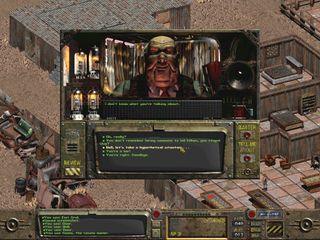

Considering the fact war never changes, it might be surprising how much the Fallout series has transformed over the past two decades. Beginning life as an isometric CRPG bathed in the glow of both tabletop and pen-and-paper role-playing games, as well as its spiritual antecedent Wasteland, the series became a world-beater.

From visual improvements to all-new quests, weapons, and gear, don't miss our list of the best mods for Fallout 4.

Going back to the first game now is an initial exercise in frustration—1997’s Fallout was, and remains, a brutally difficult, uncompromising game. If you mess up, you die. If you make the wrong decision, you die. If you don’t mess up or make the wrong decision, you still die. It’s dark, it’s (generally) presented with a straight face, and it wants you to know that the end of the world via nuclear holocaust is as cruel and vicious a thing as it sounds.

“I had been a post-apocalyptic fiction fan since I was a kid,” Brian Fargo, executive producer on Fallout (and founder of Interplay) tells us, “And Wasteland was my first attempt at bringing something to the genre. Shortly after finishing the Wasteland game, Interplay became a publisher and we no longer created games for other people. I tried to get EA to license me the rights back, but I was unable to succeed despite trying for many years. I finally decided we’d do our own post-apocalyptic game and call it Fallout.”

We were all working together in the same direction. There was little clash of egos.

Tim Cain

Sitting down with the development team, Brian Fargo and his crew at Interplay analysed what made Wasteland tick—what it was about the then-decade-old PC RPG that had kept people playing it so much over the years. “It was a matter of getting a small team to start bringing the project to life. To breathe humanity and charm into the game,” Brian remembers. “We created a sensibilities document that spoke to points such as moral ambiguity, tactical combat, a skills based system and the attributes system. After we nailed down what was important, development went off and began working on ideas that hit the touch points.”

Tim Cain is credited as the creator of Fallout—after all, it was his work on the game’s engine that brought the world to life, with a dedicated stretch of months working alone to get the project off the ground. Early versions saw time travel, and use of the GURPS ruleset that was implemented and ultimately abandoned (more on that in a minute). “I was working on different engines while nominally tasked with making game installers,” Tim explains. “I made a voxel engine, a 3D engine and finally an isometric sprite engine that I really liked. From there, I started making a combat engine based on GURPS, which I was playing paper-and-pencil with a group two or three evenings a week. That started getting some people interested in after-hours work on the game, and that grew into Fallout.”

It sounded straightforward, but development was impacted by the fact Interplay didn’t put much stock in the project. “The game did not follow a formal development process at Interplay,” Tim says. “It sort of grew organically, collecting people as it did so and avoided two near cancellations as the administration felt those resources would be better spent elsewhere.” The ‘elsewhere’ in question being big licences the studio had acquired, which it saw as the better financial option for a potential release. But Tim continued, as did a team of around 30 people, on crafting something new and original—albeit something that originally began life riffing on Wasteland.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

One system introduced in the original Fallout was a bespoke creation, and has remained one of few constants in the series: SPECIAL. Strength, Perception, Endurance, Charisma, Intelligence, Agility and Luck all came into play in shaping your character—you might have gone for a brute with low IQ, making you unable to converse with smarter NPCs, or maybe you wanted to solve everything with your wit and suave, charismatic nature: the tools were set with this deceptively simple formula.

And it almost wasn’t to be. “Fallout was originally a GURPS game,” says Chris Taylor, lead designer on Fallout. GURPS was a tabletop system developed by Steve Jackson Games; standing for Generic Universal Role Playing System, it was made to be used across all forms of role-playing, and the folks behind Fallout thought it would be a great fit. GURPS was licensed, and work began on Fallout: A GURPS Post-Nuclear Adventure, as it was called early on.

Things didn’t turn out well, though. “We showed the opening movie with the prisoner being shot in the head while waving at the camera and Steve Jackson was not fond of it, to say the least,” says Brian Fargo, “I knew the kind of world we were building and that opening scene was just a warm up to the brutal world of Fallout, so I terminated the deal.”

Needing a replacement, Chris Taylor turned to a nascent ruleset he’d been working on in his own time. “I wrote my own RPG system on the back of three-by-five cards, in notebooks and on scraps of grid paper. My game was called MediEvil. It was not good. So [my friend and I] played D&D instead. But I kept those notes and would work on the game every now and then for a decade—when it came time to replace GURPS, I had something to work with,” he says.

“The team took the system and made it work. We took it and adapted it; it had the statistics and skills we needed, but Perks were created specifically for Fallout to replace the GURPS advantage/disadvantage traits.”

This lent itself nicely to the mythos behind what Fallout would become. “The team on Fallout had a very special vibe,” Tim remembers, “We were all working together to go in the same direction. There was very little clash of egos or desire to pull the game in a different direction. That is rare in development.

“Fallout was always seen as a B project at Interplay,” he continues, “At least until the last few months of development. It is frustrating to see something in your game that no one outside the team can see until almost the last moment before it is complete.”

The team could see it, though, and those who played Fallout were treated to a deep, original, and incredibly bleak look at a world ravaged by nuclear war. Survival was hard, but you were presented with more than just guns and knives to make your way through the world. Your words were just as deadly, and the game’s final boss encounter could see players with high enough charisma talk the big bad into killing himself after convincing him of how wrong he was. This was unprecedented in computer gaming at the time, and was testament to the incredible work Tim Cain and the team carried out.

Before the original had even released, however, work on the sequel began. “Fallout really caused a buzz in the studio about six months before it was released,” Tim explains, “QA staff were coming in nights and weekends, on their own time without pay, to play it. So Fallout 2 was started even before Fallout shipped.” A small project for Interplay had become a labour of love for those working on it, and when the review scores—and money—did start coming in for the first game, it became a labour of business love for the brass at the publisher, too. Fallout 2 would launch exactly one year after the original.

Safe now in the realms of 20-year-old rose-tinted reminiscence, we remember the sequel fondly and laugh at its more light-hearted take on the series.

“Behind the scenes you will always find that it’s very intense with the creative leads battling for their perspective,” Brian says, “But that is nothing more than the creative process at work. Getting Fallout 2 off the ground was a bit painful but other than that I don’t have any specific memories of negative things. It was an all-star cast of talent all pulling in the right direction.”

One factor that stood out more than others was the fact Tim, along with two other big names in the first game, Leonard Boyarsky and Jason Anderson, all quit developer Black Isle Studios during Fallout 2’s creation. While based on ideas from the three—“We just left work for a whole day and brainstormed until we came up with the right design, which, if I recall correctly, was accepted as is without any revisions,” explains Leonard, art director on the first game—it had become a project pushed by corporate desire rather than personal motivation, with an exceedingly short development timeframe for such a huge project, and a leadership vacuum in the wake of Tim and co’s leaving.

“We had no idea any of this was going on,” says Chris Avellone, designer and writer on Fallout 2 and New Vegas. “Next thing we knew, Feargus [Urquhart] was calling an emergency meeting in Black Isle and rapidly passing out area designs for Fallout 2, splitting the game areas up amongst the available—and even unavailable—designers. We all got drafted and got to work. I was working on Planescape: Torment at the time, so my double-duty on two RPGs began.

“It did feel like the heart of the team had gone,” he continues. “And all that was left were a bunch of developers working on different aspects of the game like a big patchwork beast—but there wasn’t a good ‘spine’ or ‘heart’ to the game, we were just making content as fast as we could.”

That patchwork approach to development led to a tonal clash throughout Fallout 2. Where the first game was dark, the second included wacky references to Monty Python, Hitchhiker’s Guide To the Galaxy, Godzilla and more. Some were genuinely funny, sure, but plenty were off-target. “I think the loss of Leonard and Jason accounted for a lot of the loss of the dark tone,” Tim Cain explains. “And my personal rule of ‘no jokes or cultural references that made no sense to the player who didn’t understand them’ was thrown aside after I left development.”

“Fallout 2 was a slapdash project without a lot of oversight. Management didn’t have the time,” Avellone says, “As a result, people just threw in things they thought were funny—even things like character models you didn’t know what you were going to get.”

The fedora and Tommy gun-toting thugs in New Reno, whose character models don’t even look like they belong in the game, were presented to Chris Avellone without him even asking for them. “They were just done,” he explains, “And I had to make use of them even though they didn’t have the right ‘feel’… but then again, not much of New Reno did, even though there were a lot of things you could do in town.”

There was a lot to do throughout all of Fallout 2. The game itself wasn't terribly different from the first, but it was still a lot of fun, and the tonal differences with the first game actually amassed an army of diehards demanding humour in their Fallout games to this day. And when Fallout 2 wanted to do serious, or wanted you to see the consequences of your actions—well, just check what happens when you get ‘slaver’ tattooed on your face for a lark (spoiler: you essentially ruin your game as hardly anybody of importance will deal with you).

We wanted to more fully realise a vision of a post-apocalyptic future.

Gavin Carter

Fallout 2 released after around a year of development, compared to the original’s three years. In that time the team made a new part of the world to explore, a vast amount of new stories to tell—they even gave you a car. It was an impressive feat, yet still one that rubbed some Fallout diehards up the wrong way. Fallout’s creator, though, remained positive even though he’d left the project: “I have always been impressed that the team could make a game that was much bigger than the original in a third of the time,” Tim Cain says. “They should be enormously proud of their achievement.”

The problems arising through Fallout 2’s confused development would set a pattern for the years to follow at Interplay, and the second game would end up being the last core title in the series by the publisher. Though that’s not to say it didn’t try launching a bunch of projects, but ultimately these didn’t get off the ground. In the period between the second and third games came a couple of releases: one with some good ideas; one best left forgotten. But whatever the case, Fallout was long from being pronounced dead.

In 2001, Fallout Tactics arrived—a spin-off focusing entirely on the combat aspects of the original two games, it was a decent foray into a world like Jagged Alliance, though the ‘tactical’ aspect went down the drain a bit and it ended up being a lot more run-and-gun than might be expected.

“I was very happy with what the developer Micro Forte did with Fallout Tactics,” Chris Taylor, who acted as senior designer on the game, says, “But I’ll admit that it wasn’t exactly the game that we envisioned early in the project’s preproduction. When games are nothing but ideas, it’s easy to get excited about the concept of a game. Then reality usually steps in. Compromises are made. In Fallout Tactics’ case, it shipped earlier than it should have. It could have used a little more time baking.”

While Tactics was appreciated by some, and has grown in reputation as the years passed, the other spin-off Interplay managed to get out—Fallout: Brotherhood Of Steel—was less well-received. A consoleified version of Fallout similar to Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance, the game was, at best, dull. At worst? A stain on the reputation of the series. But Interplay wasn’t just focused on the spin-offs—it was working on an actual Fallout 3.

Codenamed Van Buren, Interplay’s take on Fallout 3 never made it to a finished state before it was cancelled. “Brian Fargo was gone by that point,” Chris Avellone explains. “And the vision for the company went along with him. And while we knew the company needed to turn a profit, we were starting to feel it in the trenches.” The first Fallout 3 was cancelled, and ultimately the franchise moved on to new owners, with its original custodian Interplay—eventually—losing all rights to Fallout.

In 2008, Bethesda, the studio behind the Elder Scrolls series of first-person role-playing games, released its own version of Fallout 3. It was a massive hit, immersing players in a post-apocalyptic wasteland (obviously) of Washington DC—changing things up significantly, while at the same time keeping the fundamentals, like the SPECIAL and VATS targeting systems, as they were. It was brand new and exciting, while at the same time completely familiar.

“There was always a desire in those days to make Bethesda Game Studios into more than just ‘the Elder Scrolls team’,” explains Gavin Carter, lead producer on Fallout 3. “There was a lot of musing about what might make a great second project. I don’t recall the exact moment I found out that it was going to be Fallout, but it was definitely in our conversations. I remember it moved quite rapidly from ‘wouldn’t it be cool if…’ to ‘maybe there’s a chance but don’t get your hopes up,’ to ‘time to start project planning.’”

Fallout 3 presented a detailed, vast world placed right in front of the player—and a shift back to the more straight-faced serious tone of the original game. After all, war is supposed to be hell. It was an intentional move in tone, Gavin tells us, because—while the second mainline Fallout game is an all-time great—these things felt like distractions to the team at Bethesda. “We wanted to more fully realise a vision of a post-apocalyptic future,” he says, “And felt that too much humour pulled you out of the experience more than it contributed.”

The move into sci-fi, away from the studio’s usual fantasy, was a challenge the team was willing to take on. While its detractors would call it ‘Oblivion with guns’, the fact is Fallout 3 was a huge accomplishment for Bethesda and the series as a whole. And it was a positive experience for the team working on it too, contrary to the years previous over at Interplay: “I remember watching people work for months to get the ending Liberty Prime sequence just right,” Gavin Carter says, “The PS3 team crunching for weeks to fix a VATS crash bug, playing VATS after Todd [Howard] and a programmer and artist huddled on it for two weeks and finally got it working well… concept art feedback meetings—‘That minigun looks way too much like a Dyson vacuum, sorry,’ walking by cubicles and seeing our VFX artist with a curtain and a warning sign up because he was gathering gore reference, the first time we got dismemberment working and were blowing up 3D people over and over again.”

Bethesda would next return to its Elder Scrolls series, moving on to what became Skyrim—but it didn’t want to leave Fallout behind, so it turned to Obsidian Entertainment, a studio made up of many folks who worked on the first two Fallout games, as well as the cancelled Van Buren. “The team was working on Fallout 3 DLC and getting ramped up and excited about Skyrim,” Gavin explains. “So they understood we couldn’t do everything on our own. I think people also realised that the choice to work with Obsidian, given their history with the franchise and the quality of work that they do, was a smart one.” Fallout: New Vegas was the ultimate result, arguably the best modern entry in the series, though it had its development challenges too.

Most Popular