The Joy of Text

While StoryNexus, Inklewriter and a number of other systems offer the ability to create worlds without any programming, something no technology can get around is how long it takes to write a game. Fallen London for example has over 812,000 words – the equivalent of eight regular novels, or one prologue by George R R Martin. Given the small size of the audience, why not just write a book instead?

“Novels are amazing and interactive stories won't replace them,” says Ingold. “But there are things interactivity lets us do that novels don't. Exploring is one – in novels, you see the world but only as a background for the action: if you really loved the Mines of Moria, you can't hold up Frodo to delve deeper. In Sorcery , there's a whole world to travel through, and the interactivity can let you do that.”

What you definitely shouldn't expect is to make a fortune via this route. “You see some one-off attempts, but at this point few people are trying to make money writing IF,” says Granade.

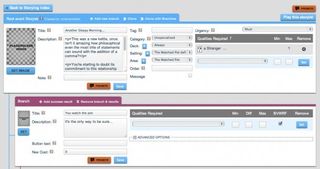

There are ways though, especially with the most recent services out there. StoryNexus offers the ability to sell content using an in-game currency called Nex, split between service and creator. Inklewriter games can be converted to Kindle books for £5 and then sold on Amazon like any other service. Both Kennedy and Ingold are more upbeat about the profit side of things. StoryNexus recently sent its authors their first payments, and Ingold is currently at work on the aforementioned Sorcery – his second iPad game – which converts the old Fighting Fantasy series of the same name to a new format.

Kindle and iPad are easily the best thing to happen to text-based games in years, not simply because these devices are great at handling words, but because monitors aren't. Longform reading on the web doesn't suffer only because of reduced attention spans or the world falling into philistine illiteracy, but because settling down in your office chair to read a long text on a monitor is as uncomfortable as finding your mother's dog-eared copy of Fifty Shades Of Grey in a shoebox under the bed.

Some games find ways around this. Fallen London's card system and limited number of turns per session make it a bite-size experience, for example. But web browsers and big screens will never be an ideal configuration for most readers, and so the focus is moving elsewhere.

“People can get lost in their iPads and their Kindles for hours,” says Ingold, who recently launched an iPad conversion of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. “As designers, we're going to have to have to adapt to make ourselves fit the tablet model, too.”

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

Kennedy goes one step further. “The natural medium for story on handheld devices is text. You can tell story through game, through video, but reading is such a natural activity on a handheld device that I would expect to see growth there.”

Even if the games themselves move away from the PC, in search of more comfortable screens and more pocket-friendly formats, it'll still be the PC (and Mac, of course) where they're written and curated. To move away from graphics isn't the easiest of things, and finding your style of game can require work. Take the time though, and you will be rewarded with some of the more imaginative stories on the PC – and potentially a creative new way to show off your writing and design chops.

Most Popular