Smart Casual - How PopCap conquered casual gaming

Real development didn't begin until 2004, when a coder at PopCap named Brian Rothstein developed a simple 2D physics engine. The talk quickly turned back to pachinko. Sukhbir thought that if they merged it with pinball or billiards, they could mix luck with skill.

“Brian created an editor that allowed us to create any kind of game like that. It was a 2D physics editor with bouncy ball physics, and we could put all sorts of objects in the game – we could put flippers there, we could do the shooter. So we ended up spending about three or four months prototyping different game ideas that were very pachinko-like, or very pinball like, or in-between. We were trying to find something that was fun, accessible, and simple."

Experimentation is key to everything PopCap do. For those first months, it was just Sukhbir and Brian working on the game – though John Vechey contributed a couple of prototypes. They'd try out some ideas, invite the entire company to play it, solicit feedback, and then iterate. I've yet to find another casual game developer that works that way.

“Jason was at Pogo.com and felt they weren't making very good games because they were very structure oriented,” says John. “At Pogo to this day a game designer can do a prototype, but once they get a prototype they have to write a design doc that has every element and game design choice already made. Then a programmer programs it, and then the artist does the art.”

By comparison, Peggle was in a constant state of flux. “We got to a point where it was fun, but it was overly twitchy,” says Sukhbir. After that, “we stepped back and simplified it and had some spinning crosses instead of pegs. but it was impossible to anticipate where the ball was going to bounce.” And then, “We changed it to pegs, but it was always super frustrating.” Finally, “What if it was just 25 pegs you had to hit? I wonder if that would be fun.”

It was. Peggle finally took form after “about 300 variants.”

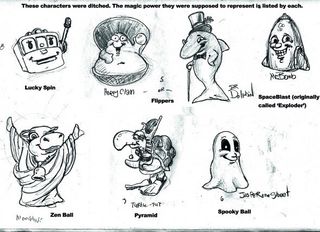

Four months in, with the concept now finished, they did the obvious thing: they spent another three years working on it. While they had their idea and it was fun, what they didn't have was a theme. They had unicorn artwork on the main menu, and Ode To Joy played when you won a game, but obviously these were just placeholders. Keeping those things in would just be silly. What the game really needed was a Thor theme. And to be called Thunderball.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

The idea was to mimic the artwork of pinball tables with Norse gods, oak wood, and fire. “50 levels of frost giants,” says Sukhbir.

Eventually they realised the charm of the original placeholder art. The design ethos became to “embrace the randomness.” The unicorn and rainbows stayed. They added a cast of other, equally bizarre characters. When the name Thunderball no longer fit, they changed it. To Pego.

PopCap's history is filled with discarded names.

It was released as Peggle in 2007 after a development process almost entirely undertaken by a team of three, and found success with both casual game players and some of the hardcore. The latter came in part because of Peggle Extreme, where you cleared levels decorated with images of Half-Life characters. It was bundled on Steam alongside Half-Life 2: Episode Two, Portal and Team Fortress 2.

“We were worried when we did the Half-Life thing, because nobody really knew how these Orange Box buyers were going to respond,” says Jason. “Some of the comments we got afterwards were, 'This is the gayest game I have ever seen, yet I cannot stop playing it.'”

“If you look at Peggle the wrong way it looks like something that's been designed by a gang of idiots for their idea of a five-year-old.”

If Peggle softened up traditional gamers, it was Plants vs Zombies that made them completely fall in love with PopCap.

The company's fifth employee, George Fan, was hired as a freelancer to make a downloadable version of his game Insaniquarium, in which you feed fish and protect them from attacking aliens. He worked on it for PopCap at night and spent his days programming Diablo III for Blizzard. “I don't suggest that anyone does programming during the day and then go home and do programming more during the night,” says George. “It's just too much using the same part of the brain. And the same part of the wrists. My wrists got really, really messed up that year.”

When Insaniquarium was complete, PopCap convinced him to join fulltime. What became Plants vs Zombies started as Insaniquarium 2. “I'm not the type who just wants to do the same game again,” George explains, “so for Insaniquarium 2, I was kind of thinking that it would be, instead of a one-fish-tank game, it would be twice the fish tank.” A double-decker fish tank.

“I don't know why that makes sense. The aliens would enter the top fish tank in hordes and they would attack your top fish, and if they broke through that they would get to your bottom fish tank. When they ate all your fish in the bottom fish tank the game would be over. The top fish tank was going to be defensive fish and depth charges, and the bottom tank was going to be the resource generator tank.”

It wasn't Plants vs Zombies, but it's not far away. Imagine that fish tank turned on its side.

It's only after returning home, when I'm speaking to George on the phone, that it becomes clear why PopCap are the casual game developers we care about. It's because they act like the very best of the traditional developers we're used to. By working at Blizzard and PopCap, George has experienced both.

“I worked at two companies that let people take as long as they wanted to make their games,” he says, with the key difference being that the smaller teams of casual game development allow for greater experimentation. “I don't think I'd be satisfied making games that everyone has played before. I think my job is to try to come up with some new experience for people to play. That happens in the hardcore industry, but it's a tougher framework.”

But maybe still not as tough as working at other casual developers. “I think when you do metrics, they're helpful, but I don't think you can rely on them,” says George. “A lot of times they'll use the metrics and they'll keep the game mechanics that help them do the best business rather than the game mechanics that create the most fun experience.”

At his keynote speech at this year's Penny Arcade Expo conference – an orgy of gaming love held at the same Benaroya Hall that houses Casual Connect – Deus Ex designer Warren Spector urged the gathering hardcore not to look down on casual game players.

He's right. It's not casual game players that we should be condemning, or the idea of approachable gaming experiences we can play at Facebook. It's the companies making these games. Most of them are not worthy of our attention or care. PopCap are.

George puts it best: “I think that the reason people want to keep playing should be that they're having a good time doing so. I think that's the slope you go down as you start designing by metric: you might lose what's truly fun about videogames.”

Most Popular