The origins of Cyberpunk 2077

What inspired Mike Pondsmith's classic role-playing game, and how that filters down into CD Projekt Red's adaptation.

When Cyberpunk 2077 debuted its new trailer at E3 this week it stepped into the centre of a debate that has trickled on for a couple of decades or so. Is cyberpunk, the literary genre that became a fashion statement, that became a pop culture touchstone, dead? Can it ever be anything more than a nostalgia trip? It’s a debate that hinges around a certain view of cyberpunk, one that sees it as a set of works that were inherently anti-capitalist, dystopian in nature, and functioned as a warning for the future of mankind at the dawn of the age of computers.

The rise of vast mega-corporations, the creation of data networks that would criss-cross the planet, the deepening of financial inequality as power and capital was consolidated among the few not the many. These were the changes that cyberpunk writers saw in our future. From the vantage point of today, we can see how many of these events have come to pass. That's why cyberpunk as a genre seems prescient, important even, as a genre of science-fiction that might be uniquely focused on the present.

But, or so the argument goes, cyberpunk works have become complacent. Rather than critiquing their futures of corporate power, inequality, and technological distortion, they have come to revel in them. New cyberpunk is shaped not by its philosophy but by its now well-worn aesthetic—rainy streets, neon signs of Japanese characters, netrunners and scummy criminals. As Bruce Sterling, one of the members of the so called “mirrorshades” group of cyberpunk writers that shaped the genre put it: “low-life, high-tech.” But that isn’t the full story, not by a long shot, and to frame cyberpunk as a purely negative image of the future, one that you would be insane to fantasise about living in, is misrepresentative.

Street life

That’s where Cyberpunk 2077 comes in. CD Projekt Red’s vast sci-fi RPG, as it stepped out of the shadows last week, did so not under the terrifying weight of total corporate control and crippling poverty, but with a sense of manic energy, ostentatious style and a violent ferocity. In the light of a recognisably Californian sun, the corporate monoliths of the Night City glowed seductively orange, while street-life flickered by at a energetic pace—fashions and styles of all colours streaking past. This is no Blade Runner dystopia, washed out by endless rain and concealed suffering. Cyberpunk 2077 is, it seems, unrepentantly slick, stylish and ready for whatever action the street has to offer. For some that might seem to contravene cyberpunk itself, but if you look to the origins of the game, the exact opposite is revealed.

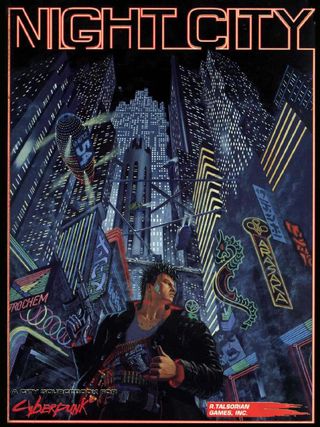

Cyberpunk 2077, as you might already know, is an adaptation. It draws directly from, and builds upon the Cyberpunk pen and paper RPG first released back in 1988, and followed by Cyberpunk 2020 in 1990. Created by Mike Pondsmith, a game designer who started his own RPG publisher, R. Talsorian Games, to release the mech-based RPG Mekton, Cyberpunk 2020 would make his name and establish a place in tabletop RPG history as the first great roleplaying game to emerge from this still new wave of sci-fi.

While by the time Cyberpunk 2020 was released Pondsmith would have integrated many elements from the Mirrorshades group, especially the work of iconic writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, Pondsmith hadn’t read either when he first started writing the game. Instead Pondsmith was inspired by Blade Runner, a commercial flop whose world he saw the potential in. This means Cyberpunk 2020 was developed in tandem with much of the core literary work that would come to define the genre. In fact, at the time of Blade Runner's release, William Gibson had yet to finish Neuromancer, and was famously terrified that people would think he had copied his book from Ridley Scott’s powerful future vision.

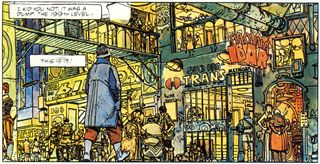

Blade Runner was a copy too however, drawing strongly from Alien writer Dan O’Bannon’s 1976 collaboration with Moebius, The Long Tomorrow. That short sci-fi comic, which follows a noir-style detective in a compressed, violent, futuristic city is the closest we have to a ground zero for cyberpunk—Gibson, Scott, and even Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo have all admitted to being influenced by its revolutionary hybrid of hard-boiled noir and urban sci-fi.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

In fact, weirdly enough, despite the half-century gap, there’s a lot of visual connections between Cyberpunk 2077’s Night City and the nameless city of the Long Tomorrow. Neither forgoes colour or light, and both glow with a sense of overlaid, intersecting, urban grit. The Long Tomorrow ends with “just another story, there are a hundred million stories in this city, this was just 12 of them” a line that might equally apply to this week’s Cyberpunk 2077 trailer and its hyperactive switching between stories and details.

Why is this a connection worth making? Because it points to an undercurrent of fantasy in cyberpunk that subverts the idea that a cyberpunk city should be a horrible place, our worst possible future. Instead, might the cyberpunk city be the ultimate urban fantasy? A city complete with all its contradictions and struggles all multiplied by a thousand, layered up across a 100 million stories ready to be explored. Breathing with an unquenchable life of its own, the life of the street.

Style over substance

That’s Mike Pondsmith’s Cyberpunk. He even has a favourite quote from William Gibson: “the street finds its own uses for things,” which points towards the ingenuity of punk, not the crushing pain of poverty. You only need to open up the gamebook for Cyberpunk 2020 to have these ideas reinforced. “As a Cyberpunk, you grab technology by the throat and hang on” it starts, in a section called “Soul & The New Machine.” The rules, the book states, are “style over substance”, “attitude is everything,” “always take it to the edge” and finally: “break the rules.”

From the get-go Pondsmith’s idea of what cyberpunk is seems to jump right out at you. It may be the “roleplaying game of the dark future” but it's a future that is only dark so that there’s something to fight against. Cyberpunk 2020’s monolithic corporations are there to be resisted, its rundown streets are there to be stalked, its technology to be deployed with a subversive flair. This is a punk fantasy, best summed up by that classic exchange from The Wild One when Marlon Brando, without missing a beat responds to the question: "What are you rebelling against, Johnny?" with "Whaddaya got?"

Cyberpunk 2077 seems nothing if not faithful to this attitude of its pen and paper predecessors. The cocky drawl the narrator offers in the trailer could have been penned by Pondsmith himself (it may well have been, as he is working closely with CD Projekt Red on the game) and the prioritising of “style over substance” is right in line with the anarchic nature of the original RPG. Not only that, the trailer is also peppered with references to some of the more extravagant ideas of Pondsmith’s: a chrome-plated diva strutting down a catwalk, eyes embedded with acrid neon, coloured mohawks, leopard print and spikes galore—these could be ripped straight out of the pages of Cyberpunk 2020.

Some of its details even are: Militech and Arasaka are two corporations pulled straight from 2020, and the trailers narrator even wears the same glow-collar jacket as the character on the cover of 2020 Night City sourcebook. It's evident that CD Projekt Red is more than just a caretaker of the series. The trailer reveals them to be avid fans, acutely aware of what does and doesn’t fit in the Night City.

A critical eye

But don’t let the swagger fool you, it's not only style that Cyberpunk 2020 put its focus on. Read further into the original gamebook, past the graphic sketches of chunky guns and reimagined '80s cars (many of which popped up in 2077’s trailer) and you get to some interesting stuff. How about a section on how corporate security used civil unrest to take control of the police force? Or how gentrification, a word Pondsmith uses well before it entered our modern lexicon, forces poor citizens into derelict sections of the city?

There’s even the Trauma Team, an overt parody of the American health insurance system, who will fly to your aid in an armoured gunship with a squad of heavily armed paramilitaries but then charge you extortionate rates for medical aid. Default on a payment and they’ll strip you for spare parts, implants and all.

These are not the ideas of someone blinded by style and disinterested in substance, but those of someone with a critical eye for the world around them, and a strong sense of how power functions. That’s something that at first glance doesn’t seem to have slipped into Cyberpunk 2077, until you look closer. Then suddenly, the hints are everywhere. News tickers discussing riots and corporate takeovers, and then, right in the middle, the Trauma Team themselves, first performing some heavily guarded CPR on what looks like a celebrity who's overdosed, and then just a scene away, bringing their gunship to a street side balcony to massacre the inhabitants of an apartment block. The system gives and the system takes away.

And perhaps it's there that we can see how Cyberpunk 2020, and by perhaps association Cyberpunk 2077 can be more than a grim warning, and instead be both an escapist fantasy and a piece of social critique. In real life there is no Trauma Team, no paramilitary private ambulance that kills or saves depending on credit rating. That idea is one far too black-and-white for reality, and instead we live in a world of greys. Occasionally someone will suggest that we already live in a cyberpunk future, that tech corporations with global reach, rising inequality and the increasingly online lives we lead are all signs that point to Gibson, Sterling and others being right. But that misses a key detail of cyberpunk worlds.

After all, these are worlds filled with characters who are able to be “off the grid”, who live lives of resistance, who use technology and the freedom of lawless places to strike back at their corporate overlords. They are empowered, strong self-defined individuals fascinated by the beautiful chaos of urban life. This is not our reality. We are instead implicated, instrumentalised, feeding data into systems we will never see the inside of, beholden to the markets that are run by others.

The idea of still using technology, but remaining separate, apart from corporate exploitation is a pipedream, and for most of us, an impossible-to-achieve goal. Meanwhile, our counter-cultures have been absorbed by corporations, making it difficult to self-define as a punk when Silicon Valley tech firms talk endlessly about “radical” concepts and “disruption” and Iggy Pop tries to sell us car insurance. But when we look to cyberpunk worlds we see an escape, we see the empowering nature of a just struggle.

With that in mind, it’s no surprise that when Mike Pondsmith tried to move Cyberpunk 2020 forward as a series, and in 2005 released Cyberpunk 203X, a transhumanist expansion of the game that posited the possible brighter future beyond corporate rule, it was a distinctly unpopular step. People didn’t want a future to look up to, they wanted one that they understood, one that allowed self-expression, daring acts, and slick style, without abandoning the sense of struggle.

Cyberpunk is about resisting, grifting, fighting and the beauty of that. Not every aspirational fantasy has to present a perfect world we might hope to attain, and not every dark future is a warning. And Cyberpunk 2020 with its focus on style and self-expression, also provided a liberating space for players, like with many tabletop RPGs, where they could self-define, and fantasise about being a slick street samurai or unshakeable punk, resistant to the dark world that surrounded them. It is this quality, if Cyberpunk 2077 can achieve it, that will make it more than a nostalgia trip, or lifeless imitation of a future that passed us by. Either way, it's difficult to accuse Cyberpunk 2077 of betraying its origins. Its future is still yet to be seen.

Most Popular