The future of dialogue in games

The challenges of writing dialogue that's both fun and functional, and how dev tools can lead to better writing.

It’s the stuff of a thousand RPGs: you’ve braved the Barren Pass and crossed the Aching Plains and now, hours since you last spoke to a coherent NPC, you’re finally standing before a city teeming with literally tens of characters, each bursting to tell you at length about the history of their people.

Getting to discover the politics and personalities of a new location should feel like a reward, but the same formulaic text dump from city to city can make you feel awfully weary. Being NPCsplained at with screeds of exposition and feeling you’re taking little meaningful part in it all, game dialogue can make you want to run back into the hills.

It’s easy to blame writers for this, but like every other aspect of videogame development, the craft of game writing is more complex than you’d think. As Adam Hines, co-founder of Oxenfree developer Night School Studio, says, "Writing for games and writing for anything else is a totally different job. It’s more like trying to solve a very complex mathematical problem than it is a pure writing exercise."

Writing for games is more like trying to solve a very complex mathematical problem than it is a pure writing exercise.

Adam Hines, Oxenfree

Oxenfree, a modern adventure game built around a group of teens chatting their way through a supernatural mystery, is a prime example of how game dialogue is getting better: more reactive, more natural, more involved, through a combination of game design and writing itself. But that doesn’t mean that game history isn’t already littered with beautifully crafted conversations which succeed at scene-setting, character-introducing, goal-orientating, and instruction-giving. Oh, and also entertaining. Game dialogue needs to do a lot.

The form must be functional

When Chris Avellone—writer and designer of games from Planescape: Torment to Fallout: New Vegas and recent free agent—writes dialogue, he thinks about it performing three fundamental things. First, the conversation needs a purpose. If it’s with a merchant, then they need to provide that service, and quickly.

Second, the dialogue needs to be aware of the narrative happening in the nearby area as well as the overarching story. "If the Enclave is encroaching on a community in Fallout, even a simple merchant can say, 'If you’ve come for supplies, you’d best hurry, won’t be much left after the Enclave arrives.’ That tells the local narrative, and the larger narrative."

And third, dialogue has to be as aware of the player’s actions as possible. "If you’ve just wiped out the Enclave, then you’d script the merchant’s opening node to something else: 'Hey, you’re the one that kicked the Enclave’s ass. Anything I have in stock; for you, half off.’"

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

For Avellone, the third part is where he finds a lot of the challenge in writing. It’s not just about crafting wonderful words, but making sure they acknowledge the player and react accordingly, and that means a lot of checking and accounting. Has the player already done the quest the NPC talks about? Has the player joined an enemy faction? "I have a checklist I go through for each character to try and make sure I haven’t forgotten anything," Avellone says. "It’s usually a matter of repeating the mantra, 'if-then-else,' again and again."

Those are the basics for dialogue in which you’re rooted to the spot, the typical way games attempt to represent the messy and responsive nature of human conversation. But some games attempt to make it more naturalistic. GTA IV, for instance, has characters who ride with you and deliver story while you’re driving to the next location, and that dialogue changes if you’re restarting a mission.

You don’t get choices, but the experience feels truer to life than a talking head and folds neatly into GTA’s existing gameflow. And in fact, it’s an idea that fits with classic scriptwriting technique.

"Aaron Sorkin said one of his writing tricks was always to have the characters talk about two things at once," says Hines. "Never have them only talking about one subject. In a game design-y way we found that really worked in Oxenfree, where if you’re having a conversation and doing something that isn’t directly tied to that conversation it feels good and like you’re patting your head and rubbing your chest. It just feels very..." He pauses, looking for the right word, but dialogue works so subtly that it’s hard to find one. "...Nice."

Having led writing on The Wolf Among Us and Tales From the Borderlands at Telltale Games, Hines wanted to reflect Sorkin’s trick, making an adventure game in which you can walk and talk at the same time. "It very quickly became apparent why every other adventure game in history is written as: you go up and you click on an interact-able and then you stand there and you have a little scene and then you regain freedom again," he admits.

That’s because players, whether they think they do or not, need dialogue to give them information about what they’re meant be doing, where they’re going, and why. In Oxenfree, you can often interrupt, choose not to respond, or simply not be listening. Part of the solution was to make the player feel like they are Alex, Oxenfree’s main character. "It’s important to us that you don’t have to think about the choices you’re making because they’re your natural responses," says Hines.

And with that comes the challenge of delivering all the exposition required to feel secure in your understanding of Alex’s world, something it solves with the device of having a stepbrother character who Alex hasn’t met before. She can relay to him (and therefore us) information about the island they’re visiting and introduce him to her friends, and it feels natural and part of the plot.

Oxenfree uses the multiple-choice format that most dialogue-based games do: dialogue options that branch off into new areas of a greater tree. Managing these trees, ensuring the player flows through them smoothly and gets the right info and tone of response for their choices, makes writing something of a technical job. "In many respects, it’s just like designing a UI," says Avellone.

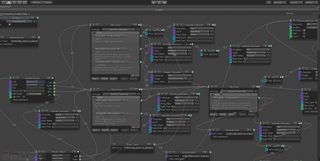

Better tools can therefore aid better writing. Avellone had to use a scripter to build conversations from Word into Fallout 2, but now dev tools often allow authoring directly in the game engine, making writing faster and playtesting a whole lot easier. As a measure of how important tools were to Oxenfree, its lead engineer, Bryant Cannon, put nearly eight months of the first year of development into creating the tool in which the dialogue was written. Resembling a flow chart, it connects all the dialogue and animations in a visual way.

But it’s a creative job as well as a technical one, and tools will only go so far. "The sad thing is that the trick is just to write a shit-ton," says Hines.

And there are practical limits to how complex a conversation can be. "If the designer can’t navigate their own conversation, it’s generally the first sign," says Avellone. "This usually happens when they’ve made the conversation too organic, have too many branches, or they don’t use chokepoints when they should." Chokepoints is the name Avellone gives to major branches in a conversation where you’re given many dialogue options, all of which will return you to that chokepoint so you can explore the rest.

And aside from the creative challenge of constructing a dialogue tree, there’s the cognitive challenge for the player trying to digest it all. "There’s a practical limit to how much text a player should be presented with, and this is even affected by if the conversation is voiced or not, since that has rules as well," Avellone says.

The Witcher 3 set a new bar for engaging dialogue and animation, and was comfortable with long conversations. It'll be hard to top. But what about dialogue out in the open world?

The future of dialogue: more ambient, more reactive

Not all dialogue in games is one-to-one. An increasingly important kind is ambient dialogue, barked by NPCs as you move through the world, giving it a sense of life. One of the ambitions Ubisoft Montreal had for Watch Dogs 2 was "to create a non-player-centric universe," according to game writer Leanne Taylor-Giles. "It naturally feels more realistic since that’s the way we, as humans, largely inhabit the world."

In Watch Dogs 2, civilians notice you running around with a gun out or if you’re doing something weird, like hiding next to a wall in broad daylight. But it’s in the details that the sense that the city is made up of people with their own agendas and problems: "For the example of the player running around with their gun out, things might get more heated if one of the nearby civilians happens to be an NRA member, for example."

The challenge for Taylor-Giles was to identify situations that people would realistically react to, as well as not writing lines for situations that are so specific that most players would never hear them. "Those moments can be great, and they are! But when you’re working with a large number of NPCs any additions become exponential." As ever, cost-versus-impact is what really decides what goes into a game.

These dynamic systems feel like they might be the future of game dialogue. "Personally, I love systems that can chain and which thereby tell a story, regardless of whether the player arrives at the beginning, the middle, or the end," says Taylor-Giles.

I often admire writers who don’t use words at all. They just work with the environment artists to build the story in the scene.

Chris Avellone

And dynamic storytelling like this doesn’t even necessarily need to be systems-led, or actually be told through dialogue. "I often admire writers who don’t use words at all. They just work with the environment artists to build the story in the scene," says Avellone. "There’s a lot you can say with just an arrangement of environment props and inventory items."

"But the emphasis also needs to be on readability," says Taylor-Giles. "Whether or not the player knows exactly what’s going on, they should be able to come up with a version of events that seems logical and realistic for the world their character is inhabiting."

In other words, developers still need to be sure that players are absorbing the information they need. But one thing that’s helping is steadily changing player expectations. Not all games give strict stories to follow and goals to accomplish, and players are becoming more comfortable with the idea of open-endedness, in which dialogue can more freely be part of the experience rather than a straightforward means to an end.

"We’re now, just in the last few years, getting out of that box and having games where there isn’t a goal and you’re hanging out and having fun and experiencing the art of them," says Hines.

As you enter that city after your long journey, what if you know that its secrets will organically unfurl as you explore it on your own terms, less being told and more feeling your way through it? Now that’d be a reward.

Most Popular