When I first encountered Soul Reaver I was blown away. If I’m honest, this was mainly because it let you kill your opponents in lots of nasty ways. Squaring off against primarily vampiric enemies, protagonist Raziel needs not only to best his opponents in combat, but execute them afterwards. This he can do by burning them with a torch, throwing them into water or a shaft of sunlight, or my favourite, impaling them with a big stick.

Soul Reaver was everything a 12-year-old boy could want, and I must have played the demo dozens of times. But I didn’t get my hands on the full game until much later, as for some reason my parents thought a game about impaling people wasn’t suitable for a child. When I finally did play the full version, I was blown away again, but for different reasons. Soul Reaver was a triumph of visual, environmental and narrative design, both a technical pioneer and an artistic accomplishment that was years ahead of its time. Indeed, its design ideas still resonate today, though perhaps not in the way you might have anticipated back in 1999.

Soul Reaver is such a singular achievement that it’s easy to forget it’s a sequel. The game continues the story of Blood Omen: Legacy of Kain. A 2D, top-down adventure developed by Silicon Knights, Blood Omen sees newly fledged vampire Kain wreak bloody vengeance upon the world that forsook him, and concludes with him ruling as self-proclaimed king of the dying land of Nosgoth.

Wraith life

Taking place 1,500 years later, Soul Reaver introduces a new protagonist. Raziel is the eldest ‘son’ of Kain (ie, the first vampire that Kain sired), who is betrayed by his father after he threatens Kain’s supremacy, apparently by growing a set of wings. For a powerful, immortal vampire, Kain sure is petty.

Left to rot for centuries, Raziel is eventually reanimated as a wraith by a mysterious entity. Now subsisting on souls rather than blood, Raziel embarks upon a vendetta, seeking out his four brothers who assisted Kain in betraying him, before tracking down the undead king himself.

It’s a dark and elegiac tale of corruption and cyclical violence. It’s also one that is exceptionally told. Soul Reaver is one of the earliest games to display a cinematic flair—not surprising given it was directed by Amy Hennig, who would go on to produce the Uncharted series. Inspired in part by John Milton’s Paradise Lost, the script is infused with an ornate style that aims to mimic its grand, oratory tone. The world is described as being “wrecked with cataclysms” and “collapsing into the dust of its former magnificence”. Meanwhile, the basic enemies you encounter are “foul, scuttling beasts”, while even doors cannot be opened without “a sigh of sepulchral air”.

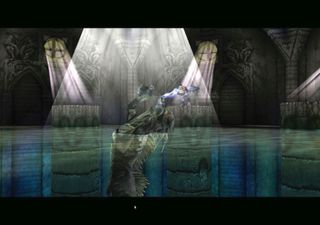

In truth, Soul Reaver’s voice errs closer to Lovecraft than Milton, and it might come across as absurd were it not so well reflected in the world’s design. Once a grand world, Nosgoth has decayed into a wasteland. The jagged ruins of landmarks like the Silent Cathedral and the Drowned Abbey loom out of the fog that conveniently reduces your line of sight to a few yards.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

At the time Soul Reaver was a technical marvel. Not only did it depict an open, 3D environment, it did so without a loading screen.

The matching of Soul Reaver’s technical limitations with the environmental art means that the game remains able to depict a certain destroyed grandeur. Locations, such as the abyssal whirlpool and the towering walls of the human citadel, still feel like threatening places. I say ‘limitations’; at the time Soul Reaver was a technical marvel. Not only did it depict an open, 3D environment, it did so without a loading screen.

Soul Reaver was one of the earliest games to take full advantage of level streaming, dividing its world into blocks which would add and remove themselves from memory as the player moved around. Clever placement of doors that trigger brief cutscenes help the game transition between larger areas, but the effect is nonetheless one of a seamless world.

Today, of course, level streaming is nothing special. But there are other tricks and effects that Soul Reaver employs which remain impressive. For example, Soul Reaver uses warp portals that allow you to transition to otherwise-disconnected areas of the world. The underlying effect is similar to that employed by Portal, albeit the implementation here is more basic. Soul Reaver’s portals are fixed in place, and your only interaction with them is choosing which other portal they’ll connect to.

Spirit realm

By far Soul Reaver’s most spectacular trick, however, is its realm transitions. The game takes place in two overlapping realms, the spectral and the physical. These twin planes of existence differ slightly in their geometrical layout, with the spectral realm being less logically coherent than the physical. Hence, when Raziel shifts between the two, the geometry of the world around you warps as well, like clay being subtly remoulded by unseen hands.

It’s a wonderful effect, but it’s far more than a visual gimmick. Phase-shifting is the basis for many of the game’s environmental puzzles. Fissures in physical walls become cavernous passages in the spectral realm, while spectral pipes and beams will twist and contort themselves into pathways impossible in physical space. Perhaps my favourite example involves a boat anchored in a water-filled ravine. Jump onto the deck and shift into the spectral realm, and the stern of the ship will skew to one side while the cliff above extends out to meet it, creating a tidy pathway.

This is just one of many ways that Soul Reaver employs spatial puzzling. Its conundrums range from Tomb Raider-like block manoeuvring to reactivating ancient contraptions, such as the colossal organ pipes of the Silent Cathedral. At a broader scale, the world itself is a gigantic enigma. Many pathways are blocked off until you attain certain powers by absorbing them from your corrupted brothers, such as the ability to climb walls or swim without dissolving.

Soul Reaver is nothing like as painful to play as the old Tomb Raider games, with generous jumps and only a moderate amount of precarious platforming.

Not all these puzzles have aged brilliantly. The block shuffling becomes tiresome after the first few instances. Moreover, the boss battles are now underwhelming. The battle against your aquatic brother Rahab is particularly unpleasant to play, as it requires you to leap between narrow platforms using the game’s slippery keyboard controls.

It’s worth noting that Soul Reaver is nothing like as painful to play as the old Tomb Raider games, with generous jumps and only a moderate amount of precarious platforming. But it has its moments. A more pressing concern for modern visitors is the game’s technical stability. I had to invest in the GOG version because my Steam copy does not work. At all.

Nosgoth extends far beyond the path that Raziel must tread to exact his vengeance. The world is littered with secrets and secondary areas that offer substantial rewards for the determined explorer. These range from health boosts to AOE attacks. Some of these optional areas are ludicrously huge. The road to the Stone Glyph, for example, sees you enter the area through the eye socket of a giant skull, before ascending the ramparts of a mountain fortress.

Reaver souls

Soul Reaver represents a curious chronological knot in the evolution of the 3D action adventure. Nowadays Crystal Dynamics is best known for having rebooted the Tomb Raider franchise twice in ten years. At the time, however, Soul Reaver was regarded as Tomb Raider’s main rival, although both series were published by Eidos. Meanwhile, as I previously mentioned, Soul Reaver was directed by Amy Hennig, whose Uncharted series for PlayStation became the main source of inspiration for the latest Tomb Raider revival.

Yet while the creators of Soul Reaver went on to define the twin pillars of action-adventure games for the next 20 years, the Legacy of Kain was left behind. The last game, Defiance, stumbled into the sunlight in 2003, and all subsequent attempts to revive the series have failed. Since then the genre has evolved along a very different route to the one envisaged by Soul Reaver, prioritising tightly scripted and explosive action over brain-scratching puzzles and a world filled with secrets.

Fascinatingly, however, Soul Reaver’s notion of a dark, difficult semi-open world adventure would anticipate a very different gaming revolution. I know its extremely passé to invoke Dark Souls nowadays, but it’s truly weird how closely Soul Reaver resembles FromSoftware’s vision, from its decaying fantasy realm concealing a mythic, ages-old conspiracy, to its highly similar system for dealing with death, and its seamless, intricately constructed environment. Both games are even fundamentally about consuming souls to become more powerful.

The similarities are such that, played today, Soul Reaver feels less like an old Tomb Raider rival and more like a missing link to Dark Souls, a discarded idea which has since been resurrected into a newer, and far meaner form. Soul Reaver was one of the last great games of the 20th century, and although the Legacy of Kain has been all but forgotten now, its spirit lives on in other bodies.

Most Popular