Censorship, Steam, and the explosive rise of PC gaming in China

A detailed investigation into where China's PC games industry is coming from, where it's headed, and what stands in the way.

There are 312 million PC gamers in China. By 2023, analysts predict that number will reach 354 million, surpassing the total population of the United States and generating an estimated $16 billion in revenue. That alone is greater than the GDP of 90 different countries. But despite having the highest concentration of gamers worldwide, China's PC gaming scene is often misunderstood or treated as isolated from PC gaming everywhere else.

But it's not.

Over 24 percent of Steam users now have their language set to Simplified Chinese and Chinese players are downloading a whopping 40 petabytes of Steam games week after week, more than anywhere else in the world. Steam isn't even supposed to be accessible in China, yet more and more often, Chinese games not localized in English are reaching Steam's top sellers list, and Chinese gamers are flocking to games not even officially released in their country. More publishers, like Ubisoft, are looking to conform to China's strict censorship regulations in hopes of reaching its lucrative market.

It's the dawn of a new era for PC gaming in China, one that is challenging both the historical conventions of what Chinese gamers want and what lengths their government will go to control their access to it.

How PC gaming took over China

[Chinese] people just didn't own games back then. The only way to play games, for a lot of people, was to go to LAN cafes.

Josh Ye

While games have been mostly free to flourish in the West, the State Council of China's communist government went to war against its own videogame industry in June 2000. Gaming consoles and arcade games were banned outright for fear of how they were warping the minds of China's younger population. But for some reason that ban didn't include videogames made for PCs. Until mobile phones revolutionized the way most people played games a decade later, PCs were the last bastion of Chinese gamers.

Buying games and hardware was prohibitively expensive, however, so many Chinese people couldn't afford to import games legitimately. "Historically there was a lot of piracy of any packaged product and a lot of counterfeit goods," says Lisa Cosmas Hanson, founder and managing partner of Niko Partners, an expert research firm for the Asian games market. "In order to make money, a company had to deliver the game as a service so that people would pay for the service instead of the software. If they were just paying for the software, they would just take the cheapest price offered to them, which in many cases would be a dollar because it would be pirated."

Below: Here are just a few of the biggest PC games in China, historically.

PC Gamer Newsletter

Sign up to get the best content of the week, and great gaming deals, as picked by the editors.

League of Legends

That League of Legends is such a global phenomenon is partly owed to its incredible success in China, which remains its largest demographic with hundreds of millions of players. League is still the undisputed king of MOBAs both in China and around the world, which prompted Tencent to buy its developer Riot Games in 2011.

Dungeon Fighter Online

This side-scrolling beat'em'up MMO was first released in Korea in 2005, but Tencent brought it to China two years later where it exploded in popularity. Today, Dungeon Fighter Online is one of the highest-grossing and most-played games of all time, with over 600 million players and $11.8 billion in lifetime revenue. Though considerably old, it still has a massive and loyal following in China.

Fantasy Westward Journey

Fantasy Westward Journey is a China-based MMO developed by NetEase and released all the way back in 2001. Across its sequels and multiple mobile spin-offs, Westward Journey boats over 310 million players around the world with China still being its largest audience.

CrossFire

Let's be clear: CrossFire is basically a Counter-Strike clone developed by SmileGate and released in China in 2008. But CS can't even hold a candle to CrossFire's incredible success: 660 million players worldwide (mostly in China and South Korea) and an estimated $10.8 billion in revenue, making it one of the highest grossing games of all time.

QQ Speed

Though not as popular as its mobile port, QQ Speed is a Mario Kart-style racer developed by Tencent that has several million players in China. Originally a browser game, QQ Speed borrows a lot of concepts from MMOs, including social features and group play.

"[Chinese] people just didn't own games back then," adds Josh Ye, a reporter with the South China Morning Post. "The only way to play games, for a lot of people, was to go to LAN cafes. It made a lot more sense to try out a game and then pay as you go. So Chinese people are more comfortable with that."

Coupled with how rare home computers were, free-to-play online games were an ingenious solution that made PC gaming accessible to all of China while still giving developers a stable way to make money. "As online games started and games from Korea were launched in China, all of a sudden this market evolved out of nothing," Hanson explains. "Keep in mind that the total market size generated from gaming in China in 2001 was $100 million and now we're at $32 billion. That is big growth."

Tencent is a Chinese megacorporation and one of the most valuable tech companies on earth, rivaling Facebook and Google. It rose to dominance on the back of its QQ and WeChat messenger apps, two ubiquitous social media platforms in China. Tencent is also the largest game company in the world, owning stakes in Activision Blizzard, Ubisoft, Paradox Interactive, Grinding Gear Games, Riot Games, Epic, and Miniclip.

PC gaming quickly became the dominant way to play games in China and free-to-play online games the favored genre, even though the wealth of China's urban populations increased significantly in the decade that followed. It's a trend driven by a voraciously competitive esports scene that accounted for 41 percent of China's PC games revenue last year. This explosive growth of PC gaming helped cement the dominance of companies like Tencent, which is solely responsible for nearly a third of China's total games revenue thanks to its PC store WeGame and the popularity of games like League of Legends. By comparison, runner-up NetEase accounts for just one tenth of the pie.

It might sound like China is a PC gamer's paradise. But that's before you hear about what it takes to release a game in China.

How China censors its games

The State Council's ban on console games was just one of the ways China's communist party sought to control its videogame market. To restrict the flow of information between China and the outside world, the Chinese government has erected a great internet firewall that blocks any content it deems unsuitable. Google searches are altered to remove offensive results and sites like Twitch and Wikipedia are blocked outright. The film Bohemian Rhapsody was heavily censored in China, removing all references to Freddie Mercury's homosexuality, drug use, and battle with AIDS.

With regards to videogames, there are two major obstacles to releasing a game in China:

1. Prohibition against foreign investment

If you're a foreign online game developer, the first hurdle is China's prohibition against foreign investment into certain business sectors like telecommunications. That law means foreign companies can't operate their own online games in China and must license that game to a Chinese company to operate it instead. It's why World of Warcraft in China is operated by NetEase and Dota 2 is run by Perfect World. Because these licensed games are operated by separate companies, they often deviate from their original versions (especially in terms of monetization) and are sometimes years behind in updates.

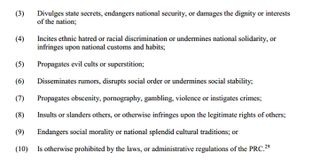

2. Vague and restrictive censorship regulations

Chinese PC gamers have long been familiar with the ways their games are altered to conform to censorship regulations. When Blizzard launched World of Warcraft in China, it famously doctored the appearance of its undead Forsaken race to make them look less dead, among many other changes. "They don't have a ratings board that says this game is for 18 and older or this game is for 12 and older," Hanson explains. "We have the ESRB, and they don't have that. Games need to be appropriate for all ages."

But the rules that any Chinese developer must abide by are often vague and unevenly enforced. For example, "anything that harms public ethics or China’s culture and traditions" and "anything that violates China’s constitution" are both prohibited in Chinese videogames.

When Tencent was unable to secure approval to monetize its mobile version of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds, it re-released PUBG Mobile as the ridiculously patriotic Game for Peace, an awkward PUBG clone that goes to almost absurd lengths to avoid drawing the ire of Chinese censors. Instead of blood, player wounds emit bright flashes of light and killed players joyfully wave goodbye instead of dying. And, seemingly to make Game for Peace less competitive, five players are declared winners instead of just one.

Once a foreign developer finds a Chinese partner to operate its online game, it still has to be approved by a regulatory government body called the State Administration of Press and Publication (SAPP).

That regulator has recently undergone massive restructuring and reforms in part because of its bitter feud with China's Ministry of Culture, the fallout of which still hangs over the games industry today. The steps China's government had to take to finally put an end to it were almost catastrophic for many developers. It's a bureaucratic nightmare defined as "Kafkaesque" by one publisher I spoke with who said the process felt "endless" and described Chinese censorship laws as unintentional attempts to "murder its own industry."

China's regulators go to war

Before the SAPP took over, two regulatory bodies oversaw the licensing and approval of videogames: The Ministry of Culture (MOC) and the State Administration of Press and Publications for Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT). The Chinese government didn't draw clear lines of responsibility for either agency, but the MOC was loosely responsible for monitoring the ongoing operation of online games, while the SAPPRFT approved games prior to release. Naturally, both saw themselves as the primary regulator of videogames and were willing to fight for it—a war that Blizzard found itself caught in with World of Warcraft's Chinese version.

In the spring of 2009, after successfully operating World of Warcraft in China for four years, Blizzard sought to terminate its partnership with Chinese company The9 and have World of Warcraft run by NetEase. When Blizzard announced the new licensing deal, both the MOC and SAPPRFT demanded that World of Warcraft be re-approved for operation in China—even though it was already approved.

What followed was nothing short of a disaster: The delay from seeking two separate reapprovals forced World of Warcraft to temporarily suspend service, shutting out tens of millions of fans. And even though the MOC finally reapproved WoW by mid-summer, the SAPPRFT took an unreasonably long time to do the same—prompting a different government body to try to solve the dispute by issuing an interpretation of the complex laws governing both organizations. NetEase took that as the green light to relaunch World of Warcraft. But when World of Warcraft servers went back online, the SAPPRFT accused NetEase of operating illegally. It was February of 2010, almost a year later, when the SAPPRFT gave World of Warcraft its approval—but only after NetEase paid a settlement and issued a public apology, of course.

That a Chinese company could find itself trapped in that kind of bureaucratic war is part of the reason why, in April of last year, the Chinese government restructured those regulatory bodies and consolidated regulatory power to one organization. Enter the SAPP, a new regulatory body with clearly defined jurisdictions and a mission to reform China's videogame censorship process. That might sound like good news for the Chinese games industry, but nothing is ever that simple.

Shutting down World of Warcraft for a few months is a minor inconvenience in comparison to the agony that the games industry endured in April to December 2018. While the SAPP was being formed, the government put a stop to all videogame approvals. China's Great Videogame Freeze saw the Chinese PC games industry shrink 2.1 percent—the first time the industry hasn't grown since 2001, according to Niko Partners. In September of 2018, Tencent claimed to have lost $190 billion in market value thanks, in part, to the freeze. But big companies like Tencent had it easiest.

Simon Zhu is the founder of the China Indie Game Alliance (CIGA) and works closely with many of China's fledgling indie developers. He tells me that the approval freeze was terrifying for many smaller companies, not that the process was easy to begin with. "[Before the freeze] it still took a long time," Zhu says. "You need many materials and you have to wait, and you have to spend money—not small money, it's big money. And now if you are waiting for a year, your studio is dead."

For many Chinese developers the wait would have been devastating if not for one mysterious hole in China's censorship firewall: Steam.

How Steam avoids Chinese censorship laws

Steam is an enigma in China. Despite the great lengths to which the Chinese government has gone to censor and regulate videogames, Steam and most of its games remain accessible to Chinese users. Only community features like forums and adult games are blocked on Steam in China. While Tencent had to recently scrap its mobile version of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds and replace it with Game for Peace, anyone in China can go on Steam and buy Grand Theft Auto 5.

I ask Hanson why Steam remains unblocked: "That's the 64-million dollar question isn't it? Everyone knows it's there and they shut down other systems, they lock things regularly as you know. How that's been continuing? I don't know."

Of the nearly half a dozen Chinese games experts I've asked, none have a certain answer why Steam remains uncensored in China, though they all have their theories. But the stakes are now very high: Steam has become a critical refuge for an estimated 40 million Chinese players and hundreds of game developers looking to escape their government's increasingly strict censorship policies and restructuring.

[Chinese] gamers love the fact that they can play games that have not gone through this approval process, which means they have a lot more variety to them.

Lisa Cosmas Hanson

During the licensing freeze last year, one game in particular soared to the top of Steam's best seller list despite not being available in English. Scroll of Taiwu became one of China's biggest indie hits after selling more than one million copies through Steam. When a reporter from the South China Morning Post asked its creator, Zheng Jie, why he chose to release on Steam, he said, "My team has an urgent need to survive." But Chinese indies aren't just surviving on Steam, many are thriving. Bloody Spell, Chinese Parents, Bright Memory, the list goes on.

"[Chinese] gamers love the fact that they can play games that have not gone through this approval process, which means they have a lot more variety to them," Hanson says. "What we used to think was that Chinese gamers would never pay for anything software related, they only wanted free-to-play games and they only wanted to pay into the in-game economy. That has changed in that Steam has allowed for a lot of options, and so they've taken the opportunity to buy those options."

But that could change soon. Last year, Valve announced it was partnering with Perfect World to create an exclusive version of Steam just for China. The implication is that this version of Steam will abide by government regulations, severely limiting its library of games to only those that have been officially approved by the government. For Iain Garner, who lives in Taiwan and co-founded Asian indie game publisher Another Indie, that's terrifying. The popular belief is that once Steam China is released the government will block the uncensored version of Steam—effectively cutting off its 40 million Chinese users from unregulated games.

"I cannot imagine that there's any way that those two platforms will operate simultaneously," Garner says. "I don't see a world in which that could happen. And that means that for a lot of developers and myself included who are relying on China for around 20 percent of all revenue, that's probably going to disappear."

Valve did not reply to our request for comment about Steam's future in China.

If Steam is eventually blocked, China's biggest, unfiltered window into western PC games will close and developers will have no choice but to conform to Chinese censorship if they want to survive. Fortunately, according to Hanson, the new reforms put in place by the SAPP are much more explicit and intuitive. The SAPP has also committed to helping guide publishers through the more transparent approval process, which should help Chinese games more easily follow the new rules.

Since April, the approvals process has begun and already the SAPP has approved more than 1,000 games, including a few foreign games. Stocks in Chinese game companies, like Tencent, are also on the rise after reaching a recent low in 2018.

But there are still many questions about what lies ahead for China's games industry, especially now that its government's grip on videogames is tighter than ever. The defunct SAPPRFT and the MOC used to be under China's State Council, itself an organization within The National People's Congress. But the SAPP is now directly under the highest censorship authority in China, the Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China (CCPPD). As Hanson puts it: "That's pretty high up. That's higher than it had been before."

And though the criteria for approval is clearer, it's also stricter. Violence was always a touchy subject and Chinese games frequently compromised by making blood a different color. But the SAPP is prohibiting blood and gore of any kind, even if it's green. And some rules are still vague, like the gentle suggestion that games should be "historically accurate."

The government's freeze on approvals has thawed, but only time will tell how rigorously and uniformly the SAPP will enforce censorship, and things are only getting more complex. Last week, Epic Games silently made its Epic Games Store available to Chinese consumers presumably without the proper government approval, effectively joining Steam as another mysterious hole through China's great internet firewall. But for the gamers and developers who have come to rely on Steam as a haven for uncensored games, and for the Chinese PC gaming industry as a whole, the future is uncertain.

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.

Most Popular